Michelangelo's drawings offer a unique insight into how the artist worked and thought. They are beautiful artworks in their own right but also provide a crucial link between his work as a sculptor, painter and architect. This ebook traces Michelangelo's life from youth to old age through drawings.

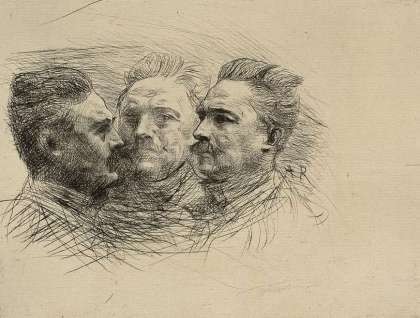

Michelangelo was extraordinarily famous during his lifetime, so much so that other artists produced portraits of him and three biographies were written. His artistic achievements set him in a class apart from his contemporaries; after the death of his main rival Raphael in 1520, he was to dominate the Roman art world for more than four decades. His primary focus as an artist was the male body, and his drawings chart his relentless search to find poses that would most eloquently express the emotional and spiritual state of his subjects.

A sculptor, architect, painter, and graphic artist, Michelangelo cannot be assigned definitely to any of those genres. The drawing as a medium for developing new ideas and conveying artistic thoughts, however, is the connecting link to and the basis of all his creative activities. During the Renaissance, drawing was established as the basis of every genre of art. Michelangelo viewed his drawings as material he needed for his work.

Contemporaries of Michelangelo collected his drawings during his lifetime and guarded them like precious gems. Presently, the total number of his existing drawings is around 600. However, during his more than seventy years of activity, he certainly produced much more, thus many works by the master must have been lost. It is well known that Michelangelo twice destroyed his own drawings: the first time was in 1517, the second time shortly before his death.

Michelangelo was extraordinarily famous during his lifetime, so much so that other artists produced portraits of him and three biographies were written. His artistic achievements set him in a class apart from his contemporaries; after the death of his main rival Raphael in 1520, he was to dominate the Roman art world for more than four decades. His primary focus as an artist was the male body, and his drawings chart his relentless search to find poses that would most eloquently express the emotional and spiritual state of his subjects.

A sculptor, architect, painter, and graphic artist, Michelangelo cannot be assigned definitely to any of those genres. The drawing as a medium for developing new ideas and conveying artistic thoughts, however, is the connecting link to and the basis of all his creative activities. During the Renaissance, drawing was established as the basis of every genre of art. Michelangelo viewed his drawings as material he needed for his work.

Contemporaries of Michelangelo collected his drawings during his lifetime and guarded them like precious gems. Presently, the total number of his existing drawings is around 600. However, during his more than seventy years of activity, he certainly produced much more, thus many works by the master must have been lost. It is well known that Michelangelo twice destroyed his own drawings: the first time was in 1517, the second time shortly before his death.

Two Male Figures after Giotto

1490-92, Pen and gray and brown ink over traces of drawing in stylus, 31.7 x 20.4 cm, Louvre, Paris

This drawing is Michelangelo's partial copy after Giotto's fresco of the Ascension of St John the Evangelist in the Peruzzi Chapel of Santa Croce in Florence. It is part of a series of early drawings in which he copied with minor alterations figures from the works of the older Florentine masters, Giotto and Masaccio. This sheet, containing anatomical studies on the verso, is regarded as the earliest extant work by Michelangelo.

1490-92, Pen and gray and brown ink over traces of drawing in stylus, 31.7 x 20.4 cm, Louvre, Paris

This drawing is Michelangelo's partial copy after Giotto's fresco of the Ascension of St John the Evangelist in the Peruzzi Chapel of Santa Croce in Florence. It is part of a series of early drawings in which he copied with minor alterations figures from the works of the older Florentine masters, Giotto and Masaccio. This sheet, containing anatomical studies on the verso, is regarded as the earliest extant work by Michelangelo.

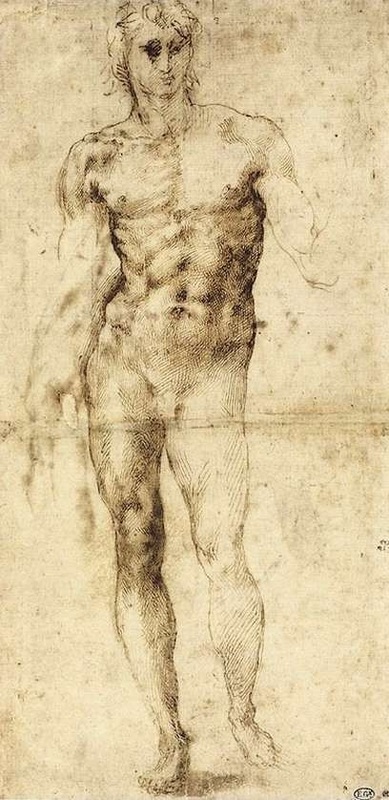

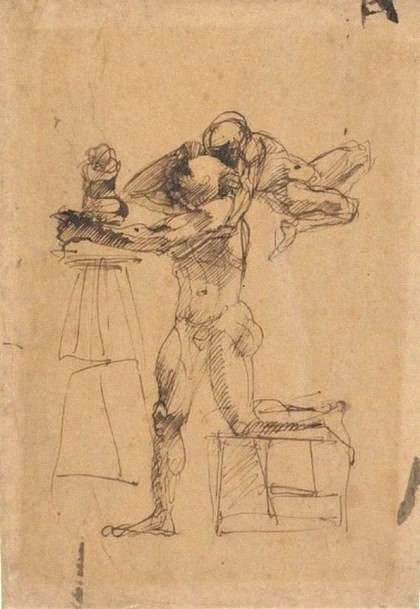

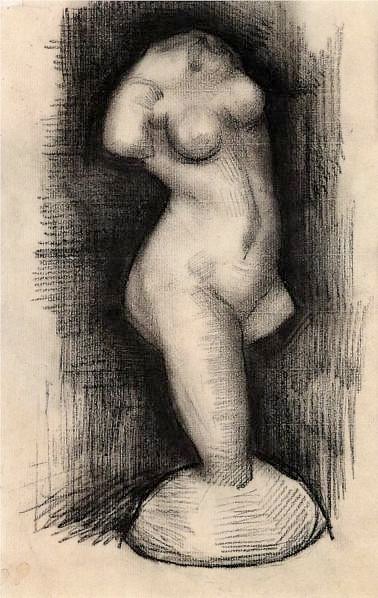

Male Nude

1501-02, Pen and brown ink, 33.7 x 16.2 cm, Louvre, Paris

This drawing, which reflects both classical inspiration and the study of a living model, is connected with the marble David, for which Michelangelo received the commission in August 1501. On the verso, various studies can be seen which can be connected to a wide variety of works by Michelangelo.

1501-02, Pen and brown ink, 33.7 x 16.2 cm, Louvre, Paris

This drawing, which reflects both classical inspiration and the study of a living model, is connected with the marble David, for which Michelangelo received the commission in August 1501. On the verso, various studies can be seen which can be connected to a wide variety of works by Michelangelo.

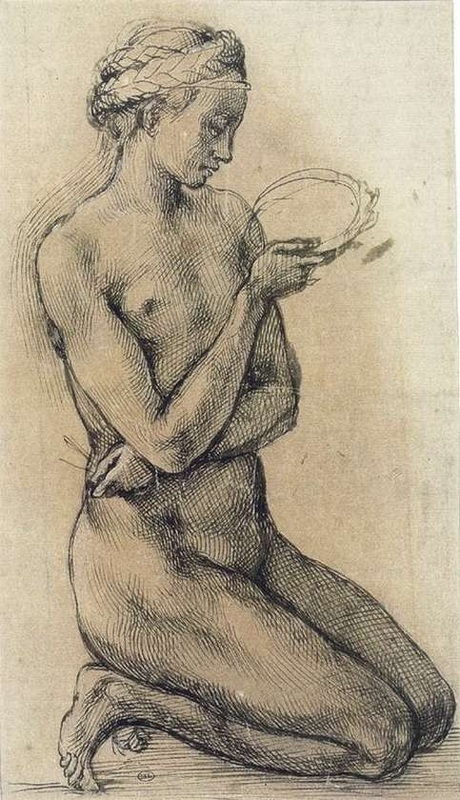

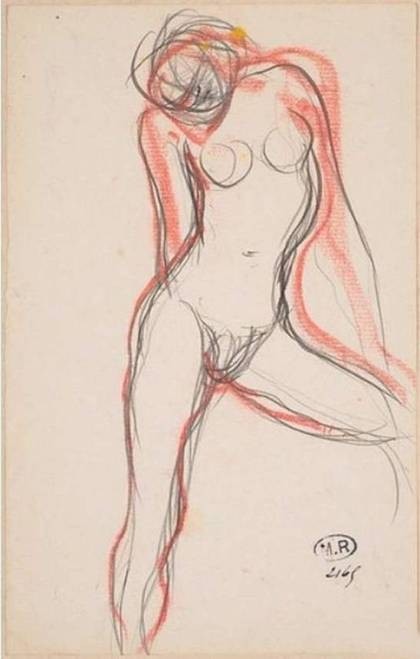

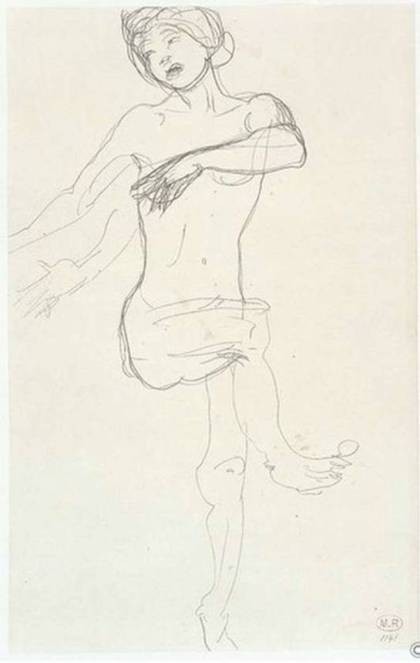

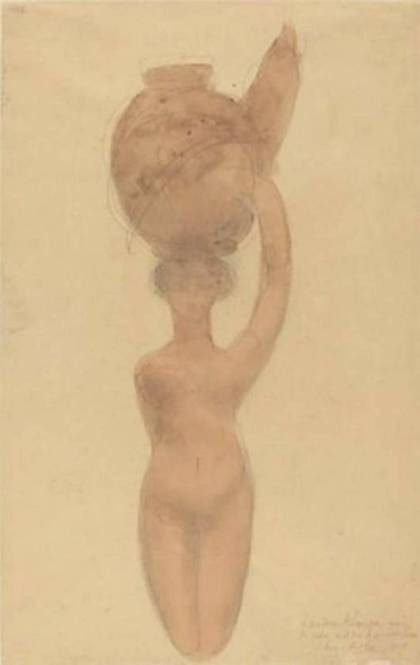

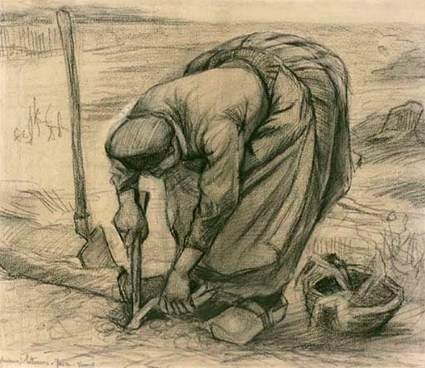

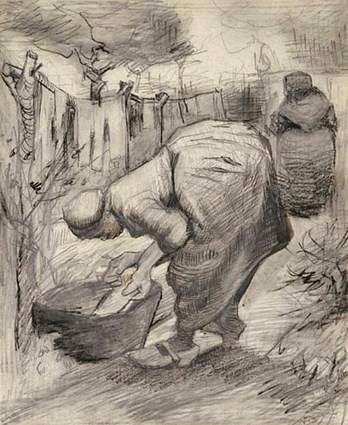

Kneeling Female Nude in Profile

1503-04, Pen and brown ink on paper partly prepared in red, 25.8 x 15,3 cm, Louvre, Paris

This female nude is a study for the kneeling woman on the left lower edge of Michelangelo's Entombment in London. The nude figure is holding the crown of thorns in her right hand and the nails of the Cross in her left, attributes that are missing in the painting, as it was never completed. On the verso of the sheet are early studies in black chalk for individual soldiers in the Battle of Cascina cartoon. The attribution to Michelangelo was often questioned in the past, the drawing was attributed to Andrea di Michelangelo, Raffaello da Montelupo, and later to the School of Fontainebleau. Indeed, Primaticcio used the motif of the female figure in France. More recent scholarship has renewed the attribution of the sheet to Michelangelo.

1503-04, Pen and brown ink on paper partly prepared in red, 25.8 x 15,3 cm, Louvre, Paris

This female nude is a study for the kneeling woman on the left lower edge of Michelangelo's Entombment in London. The nude figure is holding the crown of thorns in her right hand and the nails of the Cross in her left, attributes that are missing in the painting, as it was never completed. On the verso of the sheet are early studies in black chalk for individual soldiers in the Battle of Cascina cartoon. The attribution to Michelangelo was often questioned in the past, the drawing was attributed to Andrea di Michelangelo, Raffaello da Montelupo, and later to the School of Fontainebleau. Indeed, Primaticcio used the motif of the female figure in France. More recent scholarship has renewed the attribution of the sheet to Michelangelo.

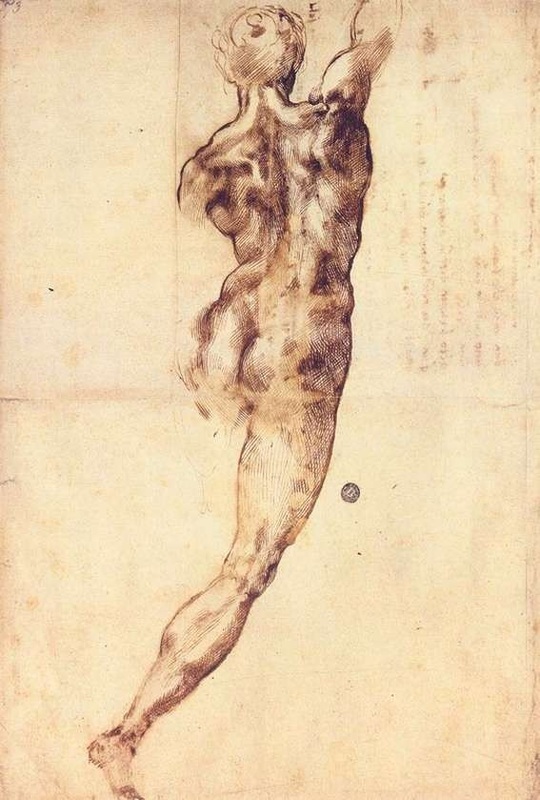

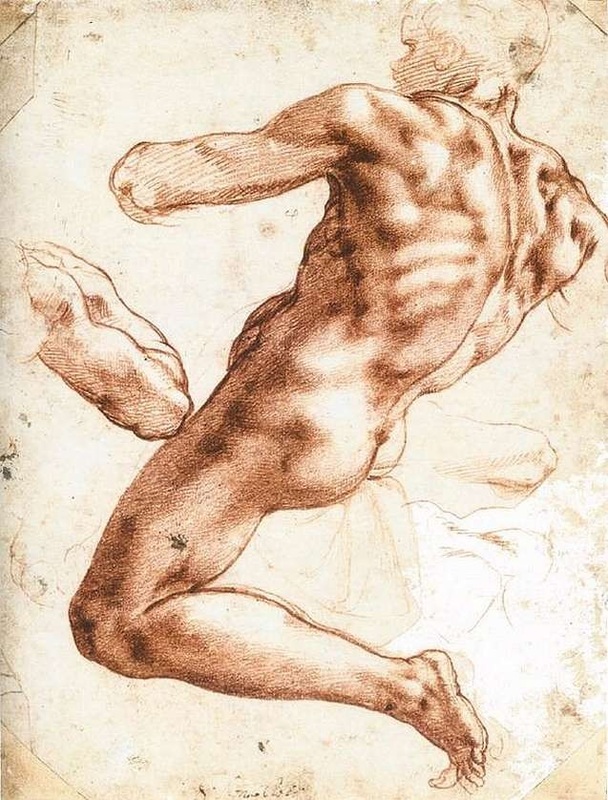

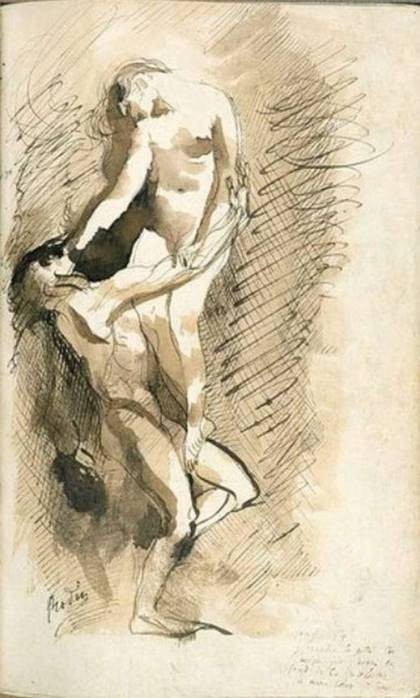

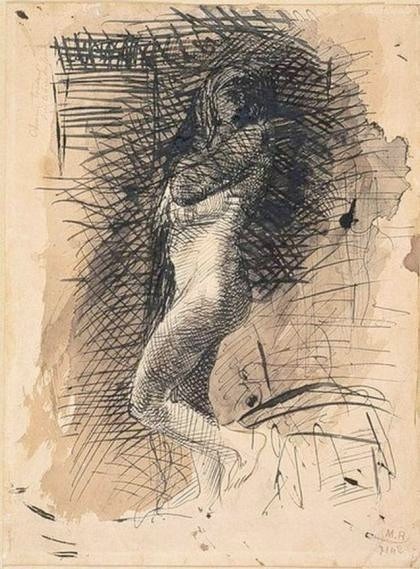

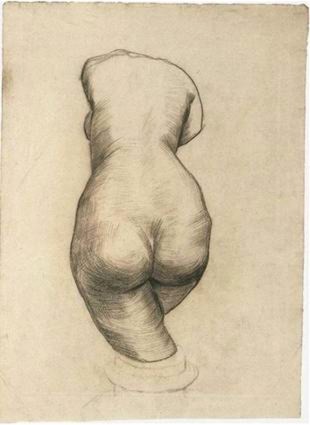

Male Nude, Seen from the Rear

1503-04, Pen and brown ink, 40.9 x 28.5 cm, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

This drawing of a male nude almost leaping toward the rear with his back arched like a bow was based on both classical and living models. It has a connection with the compositional study of the Battle of Cascina. Michelangelo kept the present drawing in his workshop, and reused it some twenty-five years later.

1503-04, Pen and brown ink, 40.9 x 28.5 cm, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

This drawing of a male nude almost leaping toward the rear with his back arched like a bow was based on both classical and living models. It has a connection with the compositional study of the Battle of Cascina. Michelangelo kept the present drawing in his workshop, and reused it some twenty-five years later.

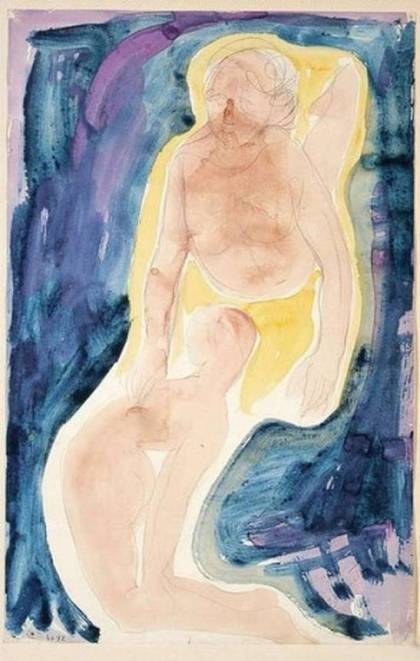

Sitting Male Nude

c. 1504, Pen and brown ink, gray-brown wash, heightened in white, 42 x 28.5 cm, British Museum, London

The present drawing on the recto of a sheet is a study for the central figure in the group of bathers of the Battle of Cascina cartoon. The figure is depicted in a complex rotational movement exploring the space around him in all directions.

The verso contains red chalk studies of figures and various legs.

c. 1504, Pen and brown ink, gray-brown wash, heightened in white, 42 x 28.5 cm, British Museum, London

The present drawing on the recto of a sheet is a study for the central figure in the group of bathers of the Battle of Cascina cartoon. The figure is depicted in a complex rotational movement exploring the space around him in all directions.

The verso contains red chalk studies of figures and various legs.

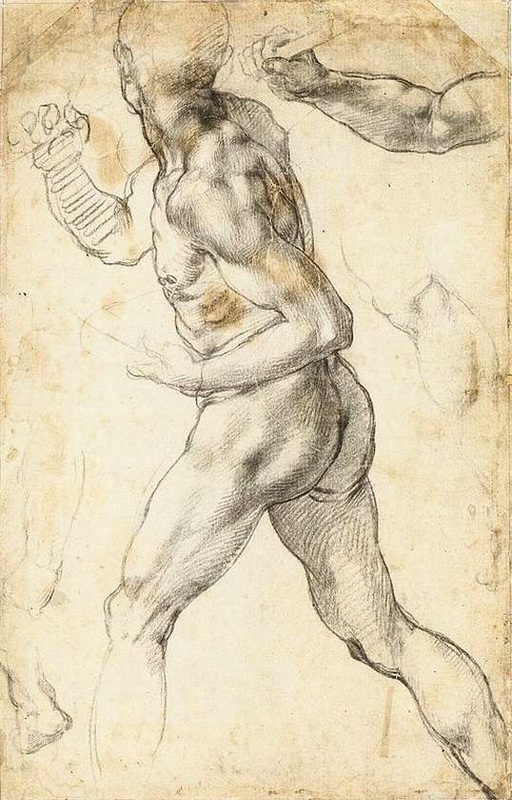

Study of a Male Nude

c. 1504, Black chalk, partial white heightening, 40.4 x 26 cm,Teylers Museum, Haarlem

Michelangelo first employed pen and ink to make studies for the soldiers in the Battle of Cascina because it allowed him to delineate individual muscles with a descriptive but agile line. But he soon became frustrated with the technical limitations and made the first set of chalk drawings of his career for the Cascina project to which this drawing belongs.

This black chalk drawing on the recto is a study for the soldier holding a lance and running into the scene at the right edge of the cartoon for the Battle of Cascina. On the verso Michelangelo drew studies of a male torso and a bent leg on a later date. These are connected with Victory group in the Palazzo Vecchio.

c. 1504, Black chalk, partial white heightening, 40.4 x 26 cm,Teylers Museum, Haarlem

Michelangelo first employed pen and ink to make studies for the soldiers in the Battle of Cascina because it allowed him to delineate individual muscles with a descriptive but agile line. But he soon became frustrated with the technical limitations and made the first set of chalk drawings of his career for the Cascina project to which this drawing belongs.

This black chalk drawing on the recto is a study for the soldier holding a lance and running into the scene at the right edge of the cartoon for the Battle of Cascina. On the verso Michelangelo drew studies of a male torso and a bent leg on a later date. These are connected with Victory group in the Palazzo Vecchio.

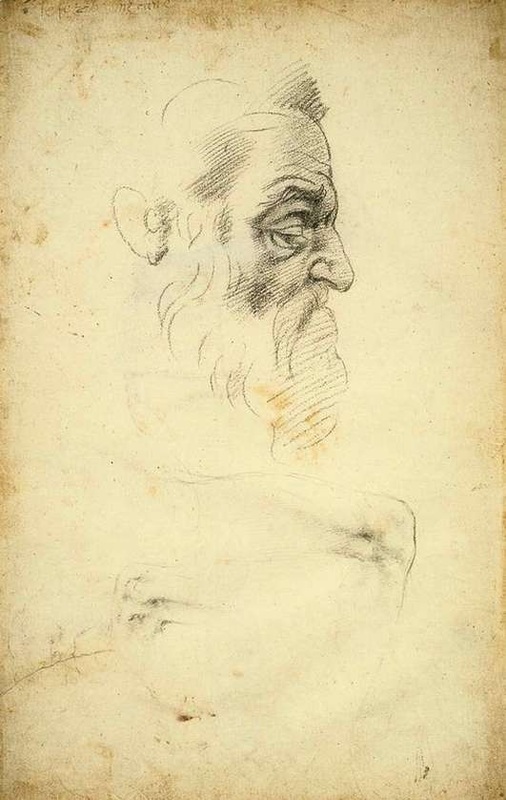

Bearded Head in Profile

c. 1508, Black chalk, 43.5 x 27.6 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The facial features of the bearded head represented on this sheet are related to the head of Prophet Zechariah, whom Michelangelo painted on the narrow side of the ceiling, directly above the main entrance of the Sistine Chapel. The face in the drawing is roughly outlined and rendered in an extremely economical manner with a few parallel lines. The studies of knee joints and legs on both sides of the sheet are also related to the ceiling frescoes.

c. 1508, Black chalk, 43.5 x 27.6 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The facial features of the bearded head represented on this sheet are related to the head of Prophet Zechariah, whom Michelangelo painted on the narrow side of the ceiling, directly above the main entrance of the Sistine Chapel. The face in the drawing is roughly outlined and rendered in an extremely economical manner with a few parallel lines. The studies of knee joints and legs on both sides of the sheet are also related to the ceiling frescoes.

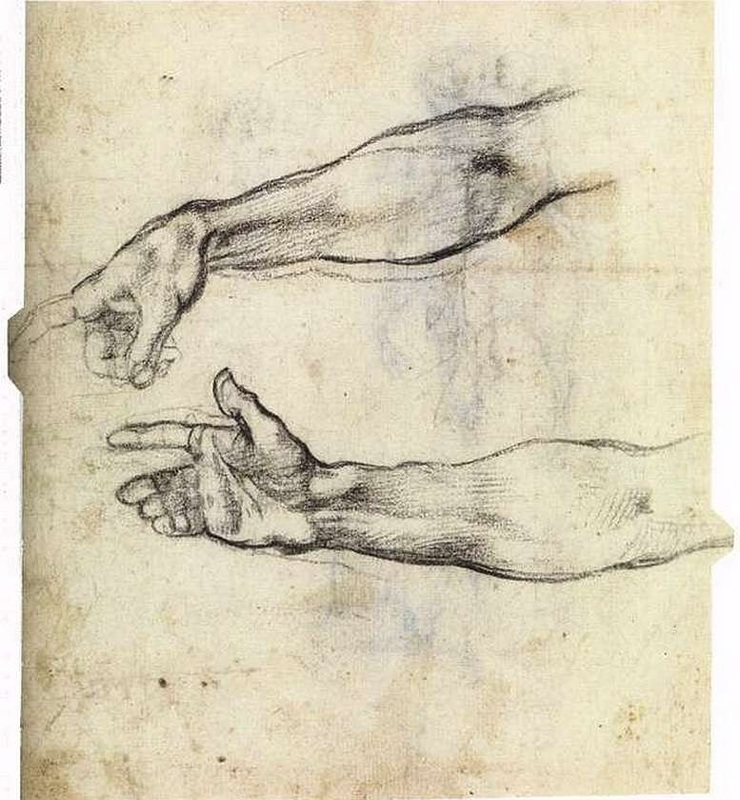

Two Studies of an Outstretched Right Arm

1508-09, Black chalk, 22.2 x 19.8 cm, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The verso of this sheet bears studies for the right arm of two of Noah's sons in the Drunkenness of Noah scene.

Michelangelo made numerous drawings in preparation for the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, but only a fraction of them have been preserved. The existence of first preparatory sketches, partial compositional drafts, studies of individual limbs and heads as well as elaborate drawings of single figures that served for the rendering on the cartoon provides evidence of the artist's careful preparation of the frescoes. The majority of the extant works are nude studies of single figures, predominantly drafts for the Ignudi. Michelangelo also created nude figures for clothed figures such as the prophets and sibyls. The only documented draft for a complete scene is the early Judith and Holofernes sketch in Haarlem. The numerous cartoons for the individual figures are lost, they were most likely among the bundle of such drawings that were burned at Michelaneglo's behest in his house in early 1518.

1508-09, Black chalk, 22.2 x 19.8 cm, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The verso of this sheet bears studies for the right arm of two of Noah's sons in the Drunkenness of Noah scene.

Michelangelo made numerous drawings in preparation for the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, but only a fraction of them have been preserved. The existence of first preparatory sketches, partial compositional drafts, studies of individual limbs and heads as well as elaborate drawings of single figures that served for the rendering on the cartoon provides evidence of the artist's careful preparation of the frescoes. The majority of the extant works are nude studies of single figures, predominantly drafts for the Ignudi. Michelangelo also created nude figures for clothed figures such as the prophets and sibyls. The only documented draft for a complete scene is the early Judith and Holofernes sketch in Haarlem. The numerous cartoons for the individual figures are lost, they were most likely among the bundle of such drawings that were burned at Michelaneglo's behest in his house in early 1518.

Study for the Head of the Cumeaen Sibyl

1508-10, Black chalk, 32 x 22.8 cm, Biblioteca Reale, Turin

This black chalk drawing depicts the head of the Cumaean Sibyl on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The head corresponds almost completely to that of the fresco, and it possibly served as the immediate model for the transfer to the cartoon.

1508-10, Black chalk, 32 x 22.8 cm, Biblioteca Reale, Turin

This black chalk drawing depicts the head of the Cumaean Sibyl on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The head corresponds almost completely to that of the fresco, and it possibly served as the immediate model for the transfer to the cartoon.

Sitting Male Nude

c. 1511, Red chalk, heightened with white, 27.9 x 21.1 cm, Teylers Museum, Haarlem

The nude study on the recto of the present sheet is a preliminary drawing for the Ignudo to the right above the Persian Sibyl on the Sistine ceiling. Drawn after a living model, the nude figure largely resembles the youth in the ceiling painting, revealing only those parts that are also visible in the fresco.

c. 1511, Red chalk, heightened with white, 27.9 x 21.1 cm, Teylers Museum, Haarlem

The nude study on the recto of the present sheet is a preliminary drawing for the Ignudo to the right above the Persian Sibyl on the Sistine ceiling. Drawn after a living model, the nude figure largely resembles the youth in the ceiling painting, revealing only those parts that are also visible in the fresco.

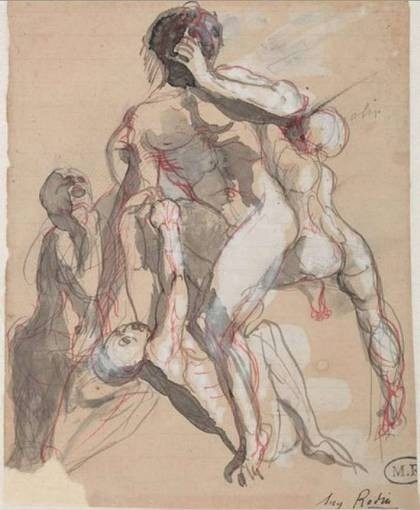

Four Studies for the Crucified Haman

c. 1512, Red chalk, 40.6 x 20.7 cm, British Museum, London

The red chalk studies on the present sheet are connected with the figure of Haman on the southwestern vault pendentive of the Sistine Chapel. For this drawing Michelangelo studied the figure on a living model and rendered it with the greatest of care, as Haman was not only the central figure of the fresco, but also gave the artist an opportunity to demonstrate a new, monumental body ideal that he had started to develop around 1510. The verso of the sheet shows further detailed studies of Haman's upper body.

c. 1512, Red chalk, 40.6 x 20.7 cm, British Museum, London

The red chalk studies on the present sheet are connected with the figure of Haman on the southwestern vault pendentive of the Sistine Chapel. For this drawing Michelangelo studied the figure on a living model and rendered it with the greatest of care, as Haman was not only the central figure of the fresco, but also gave the artist an opportunity to demonstrate a new, monumental body ideal that he had started to develop around 1510. The verso of the sheet shows further detailed studies of Haman's upper body.

Madonna and Child

1522-25, Black and red chalk, pen and brown ink on brownish paper, 54.1 x 39.6 cm, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

This large, cartoon size drawing was made on two sheets put together and trimmed on all four sides. It probably served as a model for a painting or a relief that was supposed to be executed by an other artist. There is, however, no documented evidence that the project was ever realized. This half-length depiction of the Virgin and Child is in keeping with the iconographic type of the Madonna Lactans (the Virgin breast-feeding). It is one of the most beautiful Madonna studies of the Renaissance.This drawing is one of Michelangelo's most beautiful single-figure studies and a masterpiece of draftsmanship. It is stylistically closely related to the drawings that Michelangelo presented as gifts to his friend Tommaso de' Cavalieri (The Punishment of Tityus and the Fall of Phaeton). It was probably a presentation drawing that the artist created for a specific project.

1522-25, Black and red chalk, pen and brown ink on brownish paper, 54.1 x 39.6 cm, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

This large, cartoon size drawing was made on two sheets put together and trimmed on all four sides. It probably served as a model for a painting or a relief that was supposed to be executed by an other artist. There is, however, no documented evidence that the project was ever realized. This half-length depiction of the Virgin and Child is in keeping with the iconographic type of the Madonna Lactans (the Virgin breast-feeding). It is one of the most beautiful Madonna studies of the Renaissance.This drawing is one of Michelangelo's most beautiful single-figure studies and a masterpiece of draftsmanship. It is stylistically closely related to the drawings that Michelangelo presented as gifts to his friend Tommaso de' Cavalieri (The Punishment of Tityus and the Fall of Phaeton). It was probably a presentation drawing that the artist created for a specific project.

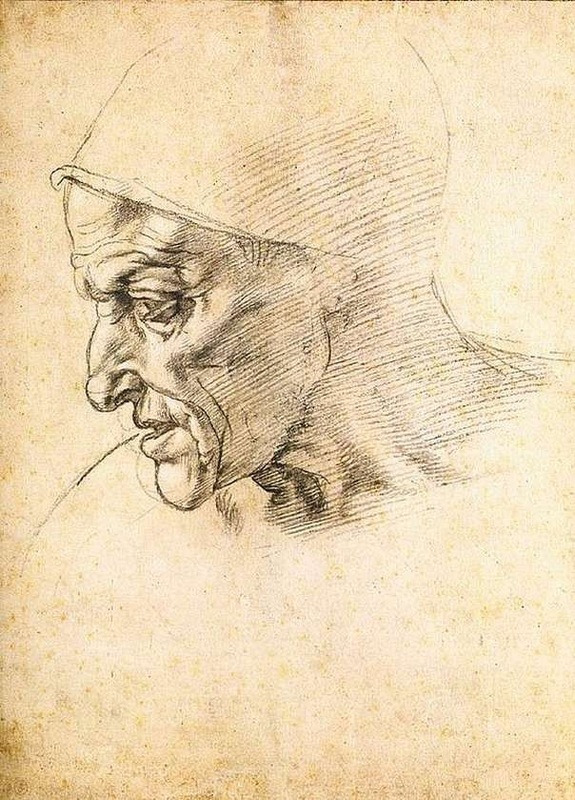

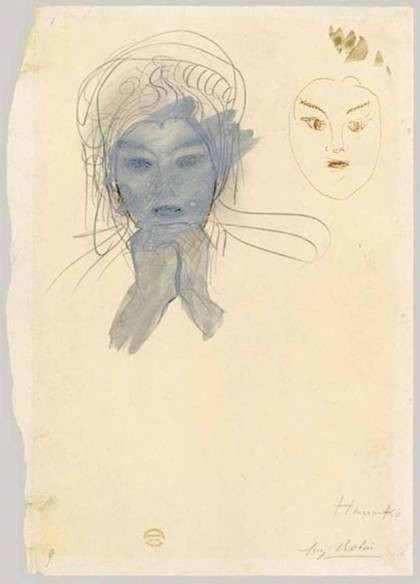

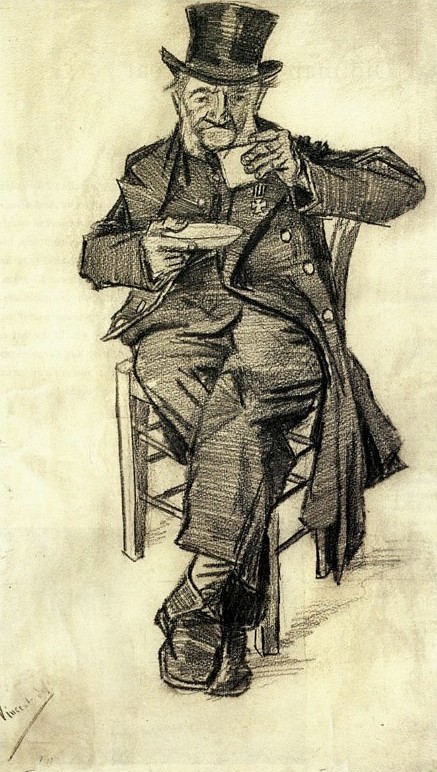

Bust of a Young Man

1524-25, Red chalk, 28.2 x 20 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

This impressive portrait is one of Michelangelo's few extant portrait drawings in which rather unattractive facial features are overstated, making them slightly bizarre in a portrayal that verges on a caricature. The intended purpose of the portrait, and the dating are subject of scholarly debate. On the verso of the sheet, a man lifting a boar is drawn in red chalk.

1524-25, Red chalk, 28.2 x 20 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

This impressive portrait is one of Michelangelo's few extant portrait drawings in which rather unattractive facial features are overstated, making them slightly bizarre in a portrayal that verges on a caricature. The intended purpose of the portrait, and the dating are subject of scholarly debate. On the verso of the sheet, a man lifting a boar is drawn in red chalk.

Four Studies of a Bent Arm

1524-25, Red chalk, 33.2 x 25.8 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The study of the backward-leaning male torso on the recto of the present sheet, as well as the studies of a bent arm on the verso can be connected with the statues of Day and Night, respectively, at the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici in the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence. On the verso of the sheet the artist rendered the right arm of the statue of Night in red chalk from four different angles. These studies, too, deviate from the finished sculpture and are not copies but preparatory drawings. Unfortunately only a few preparatory drawings for the monumental Last Judgment fresco have been preserved. Like the present drawings, there must have been numerous other study sheets on which the master prepared individual figures with utmost precision, altering or rejecting them as the final design took shape.

1524-25, Red chalk, 33.2 x 25.8 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The study of the backward-leaning male torso on the recto of the present sheet, as well as the studies of a bent arm on the verso can be connected with the statues of Day and Night, respectively, at the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici in the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence. On the verso of the sheet the artist rendered the right arm of the statue of Night in red chalk from four different angles. These studies, too, deviate from the finished sculpture and are not copies but preparatory drawings. Unfortunately only a few preparatory drawings for the monumental Last Judgment fresco have been preserved. Like the present drawings, there must have been numerous other study sheets on which the master prepared individual figures with utmost precision, altering or rejecting them as the final design took shape.

Grotesque Heads

1524-25, Red chalk, 26 x 41 cm, Stadelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

On the recto of this sheet is a group of grotesque figures, including two faun-like creatures, one looking fierce, the other bad-tempered. A third hideous face is sticking out his tongue in a mocking smile, and at the far right stands an elderly man with a hooked nose. In front of this assembly of bizarre creatures are a young man with his eyes pointed upward and a somewhat obese male in profile. The head of a startled figure is attached to him, eyes wide open and sucking on his nipple. These caricatures reveal parallels to the grotesque sculpted masks on the capitals, the surrounding frieze, and the back of Giuliano de' Medici's breastplate in the Medici Chapel. They are not, however, immediate drafts for them.

These studies show the influence of Leonardo's physiognomy studies. On the verso of the sheet, studies of the head of a woman and a child, an ear, and a leg are visible.

1524-25, Red chalk, 26 x 41 cm, Stadelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

On the recto of this sheet is a group of grotesque figures, including two faun-like creatures, one looking fierce, the other bad-tempered. A third hideous face is sticking out his tongue in a mocking smile, and at the far right stands an elderly man with a hooked nose. In front of this assembly of bizarre creatures are a young man with his eyes pointed upward and a somewhat obese male in profile. The head of a startled figure is attached to him, eyes wide open and sucking on his nipple. These caricatures reveal parallels to the grotesque sculpted masks on the capitals, the surrounding frieze, and the back of Giuliano de' Medici's breastplate in the Medici Chapel. They are not, however, immediate drafts for them.

These studies show the influence of Leonardo's physiognomy studies. On the verso of the sheet, studies of the head of a woman and a child, an ear, and a leg are visible.

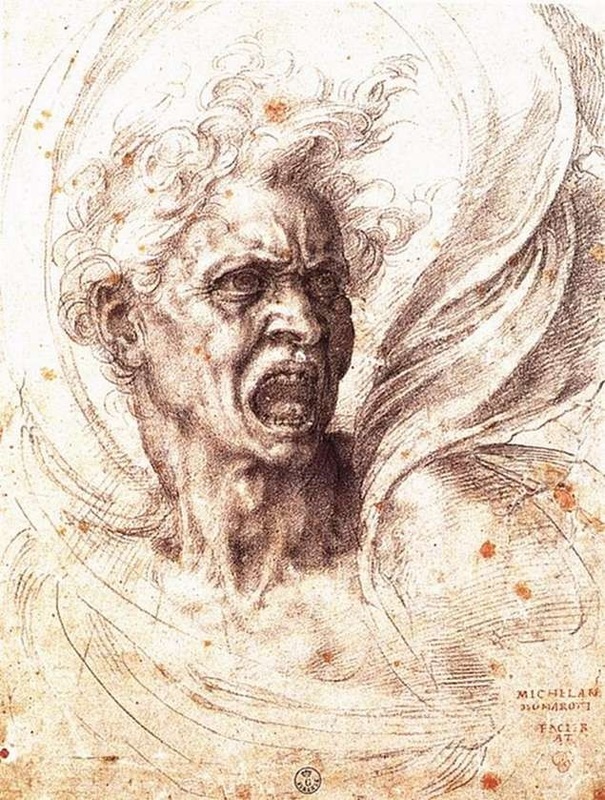

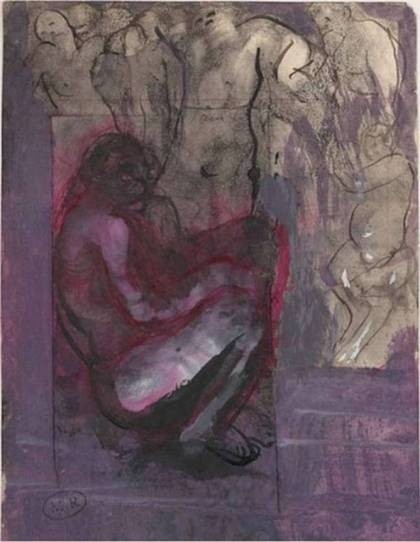

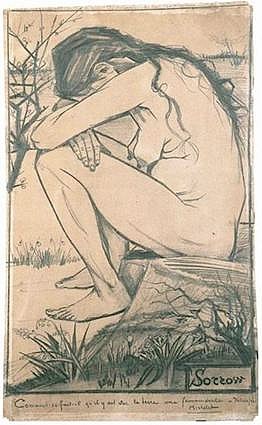

The Damned Soul

c. 1525, Ink on paper, 35.7 x 25.1 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

c. 1525, Ink on paper, 35.7 x 25.1 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

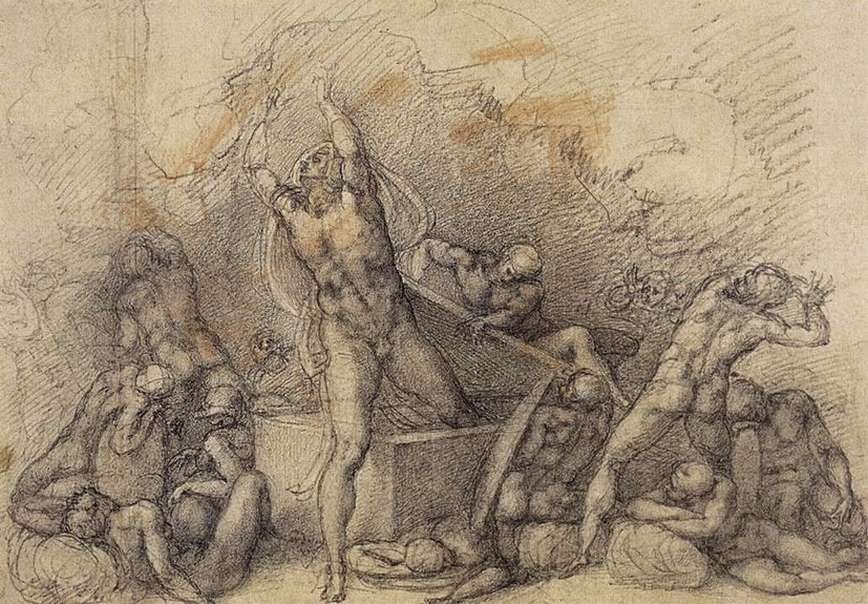

The Resurrection

1531-32, Black chalk, traces of red chalk, 24 x 34.7 cm, Royal Collection, Windsor

This representation is a rarity in Italian art in that it depicts the exact moment that Christ rises from the tomb. Although it is only a drawing, the arresting contrast between the soldiers, either cowering on the tomb or fleeing in horror, and Christ at the moment of his resurrection is still unmistakable. Without leaving the realms of the natural, the upwards movement towards the light symbolizes the Resurrection of the Redeemer.

This drawing is probably connected with the commission for the Medici Chapel in Florence. It was proposed that the drawing was a study for a painting in the lunette above the double tomb of the Magnifici at the entrance wall of the chapel. Given its pyramidal structure, the composition is suitable for a lunette. A fresco of the subject would have been required by the dedication of the chapel to the Resurrection.

On the verso of the sheet, three studies of a male shoulder are seen.

1531-32, Black chalk, traces of red chalk, 24 x 34.7 cm, Royal Collection, Windsor

This representation is a rarity in Italian art in that it depicts the exact moment that Christ rises from the tomb. Although it is only a drawing, the arresting contrast between the soldiers, either cowering on the tomb or fleeing in horror, and Christ at the moment of his resurrection is still unmistakable. Without leaving the realms of the natural, the upwards movement towards the light symbolizes the Resurrection of the Redeemer.

This drawing is probably connected with the commission for the Medici Chapel in Florence. It was proposed that the drawing was a study for a painting in the lunette above the double tomb of the Magnifici at the entrance wall of the chapel. Given its pyramidal structure, the composition is suitable for a lunette. A fresco of the subject would have been required by the dedication of the chapel to the Resurrection.

On the verso of the sheet, three studies of a male shoulder are seen.

Madonna and Child with the Infant St John

c. 1532, Black chalk, 31.7 x 21 cm, Royal Collection, Windsor

In the recto of the sheet the Madonna and Child with the infant St John is depicted. The group is arranged in the shape of a triangle, thus following a pictorial type that was popular in depictions of the Madonna in Florence in the first decade of the sixteenth century. The drawing was formerly attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, but this attribution was rejected on stylistic considerations. The intended purpose of the drawing yet has to be identified.

On the verso, a red chalk drawing of a female figure can be seen. It is not by Michelangelo's hand, the author of the drawing yet has to be identified.

c. 1532, Black chalk, 31.7 x 21 cm, Royal Collection, Windsor

In the recto of the sheet the Madonna and Child with the infant St John is depicted. The group is arranged in the shape of a triangle, thus following a pictorial type that was popular in depictions of the Madonna in Florence in the first decade of the sixteenth century. The drawing was formerly attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, but this attribution was rejected on stylistic considerations. The intended purpose of the drawing yet has to be identified.

On the verso, a red chalk drawing of a female figure can be seen. It is not by Michelangelo's hand, the author of the drawing yet has to be identified.

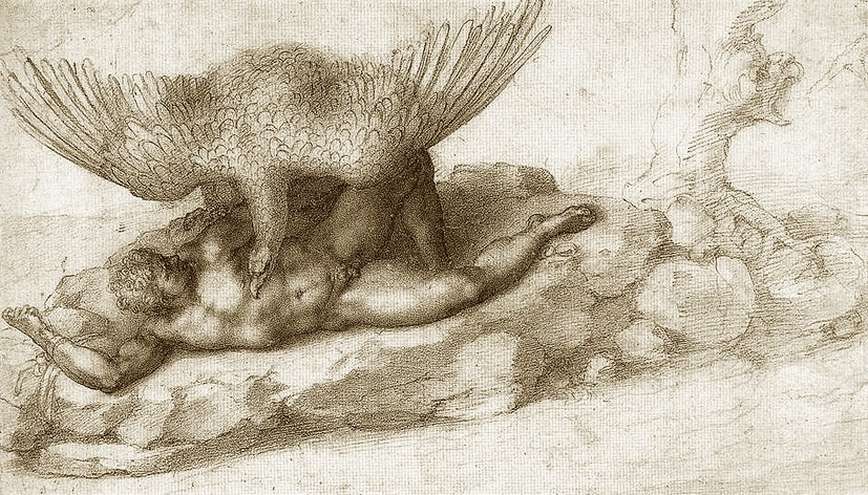

The Punishment of Tityus

1532, Black chalk, 19 x 33 cm, Royal Library, Windsor

In 1532, Michelangelo was 57 when he met the 17-year-old Tommaso dei Cavalieri, who came from a well-respected patrician family. The artist was immediately and utterly smitten by the youth's beauty, distinguished appearance, and intellect, and their meeting marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Michelangelo sent Tommaso sonnets, letters, and drawings, in which he expressed his love for him. He promoted the young man's artistic interest by teaching him how to draw and by imparting architectural knowledge to him.

Michelangelo presented as a gift to Tommaso a series of drawings on classical-mythological themes. These included The Rape of Ganymede, The Punishment of Tityus, The Fall of Phaethon. All these heroes symbolized the "fire that burned in him". According to Vasari, the master created many other drawings for Tommaso, among them the "divine heads" in black and red chalk, such as the portrait of Cleopatra.

The present drawing shows a vulture gnawing at the hero's liver. On the verso of the sheet, the artist traced the outlines of Tityus's body almost identically and turned him into a Risen Christ.

1532, Black chalk, 19 x 33 cm, Royal Library, Windsor

In 1532, Michelangelo was 57 when he met the 17-year-old Tommaso dei Cavalieri, who came from a well-respected patrician family. The artist was immediately and utterly smitten by the youth's beauty, distinguished appearance, and intellect, and their meeting marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Michelangelo sent Tommaso sonnets, letters, and drawings, in which he expressed his love for him. He promoted the young man's artistic interest by teaching him how to draw and by imparting architectural knowledge to him.

Michelangelo presented as a gift to Tommaso a series of drawings on classical-mythological themes. These included The Rape of Ganymede, The Punishment of Tityus, The Fall of Phaethon. All these heroes symbolized the "fire that burned in him". According to Vasari, the master created many other drawings for Tommaso, among them the "divine heads" in black and red chalk, such as the portrait of Cleopatra.

The present drawing shows a vulture gnawing at the hero's liver. On the verso of the sheet, the artist traced the outlines of Tityus's body almost identically and turned him into a Risen Christ.

The fall of Phaethon

c. 1533, Black chalk, 41.3 x 23.4 cm, Royal Library, Windsor

In Greek mythology Phaethon was the son of Helios, the sun-god. Helios drove his golden chariot, a 'quadriga' yoked to a team of four horses abreast, daily across the sky. Phaethon persuaded his unwilling father to allow him for one day to drive his chariot across the skies. Because he had no skill he was soon in trouble, and the climax came when he met the fearful Scorpion of the zodiac. He dropped the reins, the horses bolted and caused the earth itself to catch fire. In the nick of time Jupiter, father of the goods, put a stop to his escapade with a thunderbolt which wrecked the chariot and sent Phaethon hurtling down in flames into the River Eridanus (according to some, the Po). He was buried by nymphs. Phaethons's reckless attempt to drive his father's chariot made him the symbol of all who aspire to that which lies beyond their capabilities.

The fall of Phaethon was a popular theme, common in Renaissance and Baroque painting, especially on ceilings in the later period. Phaethon, the chariot, and four horses, reins flying, all tumble headlong out of the sky. Above, Jupiter throws a thunderbolt.

c. 1533, Black chalk, 41.3 x 23.4 cm, Royal Library, Windsor

In Greek mythology Phaethon was the son of Helios, the sun-god. Helios drove his golden chariot, a 'quadriga' yoked to a team of four horses abreast, daily across the sky. Phaethon persuaded his unwilling father to allow him for one day to drive his chariot across the skies. Because he had no skill he was soon in trouble, and the climax came when he met the fearful Scorpion of the zodiac. He dropped the reins, the horses bolted and caused the earth itself to catch fire. In the nick of time Jupiter, father of the goods, put a stop to his escapade with a thunderbolt which wrecked the chariot and sent Phaethon hurtling down in flames into the River Eridanus (according to some, the Po). He was buried by nymphs. Phaethons's reckless attempt to drive his father's chariot made him the symbol of all who aspire to that which lies beyond their capabilities.

The fall of Phaethon was a popular theme, common in Renaissance and Baroque painting, especially on ceilings in the later period. Phaethon, the chariot, and four horses, reins flying, all tumble headlong out of the sky. Above, Jupiter throws a thunderbolt.

The Lamentation of Christ

1533-34, Black chalk, 28.2 x 26.2 cm, British Museum, London

In the present drawing Michelangelo rendered the event of Lamentation with exceptionally drastic expressiveness. The depiction of Christ lying in the Madonna's lap, his head fallen back and his right arm hanging down lifelessly, is in keeping with a pictorial type common in Northern Pieta sculptures of the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Because of their dissemination by traveling German sculptors, examples of these Pier compositions were widely known in Italy as early as the fifteenth century. The present drawing is closely related to works such as the German oak Pieta in Rheinberg. Unlike the creators of such Pieta sculptures, Michelangelo expanded the scene to a multi-figural lamentation group, similar to Donatallo's bronze relief, now in London, which was certainly also inspired by Northern examples.

It can be assumed that this composition was a preliminary drawing for a painting commissioned from Michelangelo's friend, Sebastiano del Piombo.The nude figure on the verso of the sheet is probably not in Michelangelo's own hand.

1533-34, Black chalk, 28.2 x 26.2 cm, British Museum, London

In the present drawing Michelangelo rendered the event of Lamentation with exceptionally drastic expressiveness. The depiction of Christ lying in the Madonna's lap, his head fallen back and his right arm hanging down lifelessly, is in keeping with a pictorial type common in Northern Pieta sculptures of the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Because of their dissemination by traveling German sculptors, examples of these Pier compositions were widely known in Italy as early as the fifteenth century. The present drawing is closely related to works such as the German oak Pieta in Rheinberg. Unlike the creators of such Pieta sculptures, Michelangelo expanded the scene to a multi-figural lamentation group, similar to Donatallo's bronze relief, now in London, which was certainly also inspired by Northern examples.

It can be assumed that this composition was a preliminary drawing for a painting commissioned from Michelangelo's friend, Sebastiano del Piombo.The nude figure on the verso of the sheet is probably not in Michelangelo's own hand.

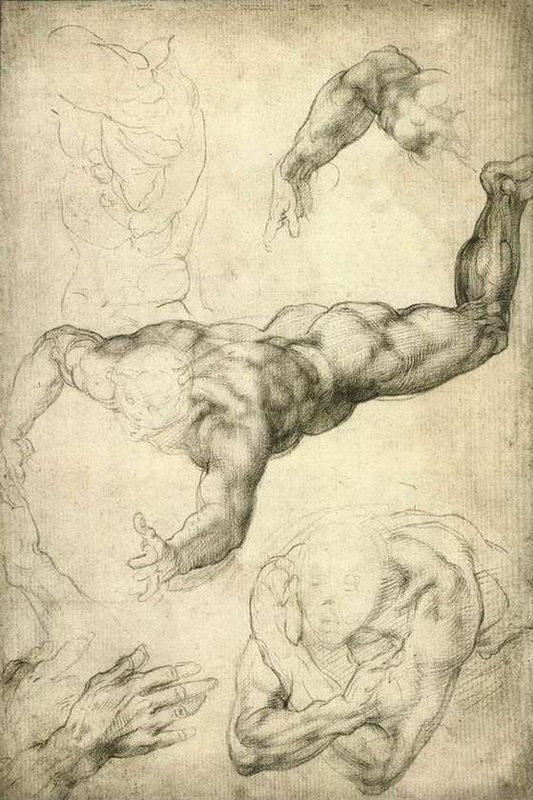

Studies for a Flying Angel

1534-36, Black chalk, 40.7 x 27.2 cm, British Museum, London

The centre on the recto of the present sheet is occupied by a study of one of the flying angels carrying the Instruments of the Passion in the right lunette of the Last Judgment. Michelangelo painted this lunette after he had completed its left counterpart, which marked the beginning of his work on the monumental fresco in 1536. Probably drawn after a living model lying flat on his stomach, the drawing differs from the figure finally executed in the fresco in the posture of the head, the position of the left hand, and the fact that the lower part of the body is not turned toward the viewer.

The verso of the sheet includes two further studies of the floating angel of the recto as well as a sketch of his left arm.

Unfortunately only a few preparatory drawings for the monumental Last Judgment fresco have been preserved. Like the present drawings, there must have been numerous other study sheets on which the master prepared individual figures with utmost precision, altering or rejecting them as the final design took shape.

1534-36, Black chalk, 40.7 x 27.2 cm, British Museum, London

The centre on the recto of the present sheet is occupied by a study of one of the flying angels carrying the Instruments of the Passion in the right lunette of the Last Judgment. Michelangelo painted this lunette after he had completed its left counterpart, which marked the beginning of his work on the monumental fresco in 1536. Probably drawn after a living model lying flat on his stomach, the drawing differs from the figure finally executed in the fresco in the posture of the head, the position of the left hand, and the fact that the lower part of the body is not turned toward the viewer.

The verso of the sheet includes two further studies of the floating angel of the recto as well as a sketch of his left arm.

Unfortunately only a few preparatory drawings for the monumental Last Judgment fresco have been preserved. Like the present drawings, there must have been numerous other study sheets on which the master prepared individual figures with utmost precision, altering or rejecting them as the final design took shape.

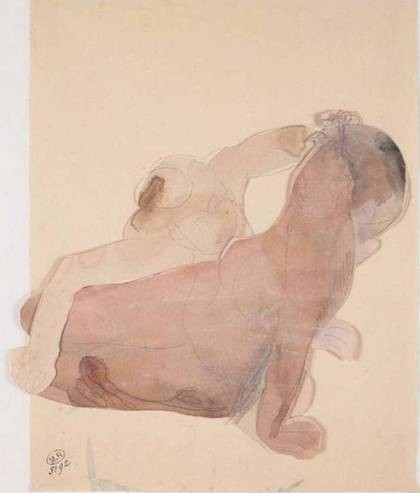

Study for the Colonna Pieta

c. 1538, Black chalk, 29.5 x 19.5 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

In 1538, three years before the completion of the Last Judgment, Michelangelo had met Vittoria Colonna. She belonged to the circle of Juan Valdes, who was striving towards an internal reform of the Catholic Church. These almost protestant beliefs could not conquer, or in any way change, Michelangelo because too much of his work would have had to be denied. However, they must have to some extent disrupted his firm belief, as he had expressed it in his works, that by creating perfect physical beauty he had represented the essence of the supernatural and of the divine. It is true, however, that he felt the need for divine grace, and, from this point onwards, this had great bearing on his creative life.

We find evidence of this in a drawing of the Pieta, made for Vittoria Colonna. When compared with the 1499 Pieta, we see clearly that the main objective is the thought of the Compassionate Christ and of the Redemption through Christ's Blood. The work turns openly towards the onlooker to admonish him, drawing his attention to the sacrifice of Golgotha.

c. 1538, Black chalk, 29.5 x 19.5 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

In 1538, three years before the completion of the Last Judgment, Michelangelo had met Vittoria Colonna. She belonged to the circle of Juan Valdes, who was striving towards an internal reform of the Catholic Church. These almost protestant beliefs could not conquer, or in any way change, Michelangelo because too much of his work would have had to be denied. However, they must have to some extent disrupted his firm belief, as he had expressed it in his works, that by creating perfect physical beauty he had represented the essence of the supernatural and of the divine. It is true, however, that he felt the need for divine grace, and, from this point onwards, this had great bearing on his creative life.

We find evidence of this in a drawing of the Pieta, made for Vittoria Colonna. When compared with the 1499 Pieta, we see clearly that the main objective is the thought of the Compassionate Christ and of the Redemption through Christ's Blood. The work turns openly towards the onlooker to admonish him, drawing his attention to the sacrifice of Golgotha.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed