Amedeo Clemente Modigliani (July 12, 1884 – January 24, 1920) was an Italian painter and sculptor who worked mainly in France. Primarily a figurative artist, he became known for paintings and sculptures in a modern style characterized by mask-like faces and elongation of form. He died in Paris of tubercular meningitis, exacerbated by poverty, overwork and addiction to alcohol and narcotics.

Modigliani was born into a Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for those persecuted for their religion, and was home to a large Jewish community. His maternal great-great-grandfather, Solomon Garsin, had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century as a refugee.

Modigliani's mother (Eugénie Garsin) who was born and grew up in Marseille, was descended from an intellectual, scholarly family of Sephardic Jews, generations of whom had resided along the Mediterranean coastline. Her ancestors were learned people, fluent in many languages, known authorities on sacred Jewish texts and founders of a school of Talmudic studies. Family legend traced the Garsins' lineage to the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

The family business was believed to be a credit agency with branches in Livorno, Marseille, Tunis, and London. Their financial fortunes ebbed and flowed. At times they enjoyed affluence, at other times they were subject to dire financial crises and reduced circumstances.

Modigliani’s father, Flaminio, hailed from a family of successful businessmen and entrepreneurs. While not as culturally sophisticated as the Garsins, they knew how to invest into and develop thriving business endeavors. Their wealth was derived from mining the metals abundant in the area of Sardinia and Tuscany and extracting and exporting the ores. When the Garsin and Modigliani families announced the engagement of their children, Flaminio was a wealthy young mining engineer. He managed the mine in Sardinia and oversaw the almost 30,000 acres of timberland the family owned. He also was expert in both forestry and farming management. A reversal in fortune occurred to this prosperous family in 1883. An economic downturn in the price of metal plunged the Modiglianis into bankruptcy. Ever resourceful, Modigliani’s mother used her social contacts to establish a school and, along with her two sisters, made the school into a successful enterprise.

Modigliani was the fourth child, whose birth coincided with the disastrous financial collapse of his father's business interests. Amedeo's birth saved the family from ruin; according to an ancient law, creditors could not seize the bed of a pregnant woman or a mother with a newborn child. The bailiffs entered the family's home just as Eugenia went into labor; the family protected their most valuable assets by piling them on top of her.

Modigliani had a close relationship with his mother, who taught him at home until he was 10. Beset with health problems after an attack of pleurisy when he was about 11, a few years later he developed a case of typhoid fever. When he was 16 he was taken ill again and contracted the tuberculosis which would later claim his life. After Modigliani recovered from the second bout of pleurisy, his mother took him on a tour of southern Italy: Naples, Capri, Rome and Amalfi, then north to Florence and Venice.

Modigliani worked in Micheli's Art School from 1898 to 1900. Here his earliest formal artistic instruction took place in an atmosphere steeped in a study of the styles and themes of 19th-century Italian art. In his earliest Parisian work, traces of this influence, and that of his studies of Renaissance art, can still be seen. His nascent work was shaped as much by such artists as Giovanni Boldini as by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Modigliani showed great promise while with Micheli, and ceased his studies only when he was forced to, by the onset of tuberculosis.

In 1901, whilst in Rome, Modigliani admired the work of Domenico Morelli, a painter of melodramatic religious and literary scenes. Morelli had served as an inspiration for a group of iconoclasts who were known by the title "the Macchiaioli" (from macchia —"dash of colour", or, more derogatively, "stain"), and Modigliani had already been exposed to the influences of the Macchiaioli.

This localized landscape movement reacted against the bourgeois styling of the academic genre painters. While sympathetically connected to (and actually pre-dating) the French Impressionists, the Macchiaioli did not make the same impact upon international art culture as did the contemporaries and followers of Monet, and are today largely forgotten outside of Italy.

Modigliani's connection with the movement was through Guglielmo Micheli, his first art teacher. Micheli was not only a Macchiaiolo himself, but had been a pupil of the famous Giovanni Fattori, a founder of the movement. Micheli's work, however, was so fashionable and the genre so commonplace that the young Modigliani reacted against it, preferring to ignore the obsession with landscape that, as with French Impressionism, characterized the movement. Micheli also tried to encourage his pupils to paint en plein air, but Modigliani never really got a taste for this style of working, sketching in cafés, but preferring to paint indoors, and especially in his own studio. Even when compelled to paint landscapes (three are known to exist), Modigliani chose a proto-Cubist palette more akin to Cézanne than to the Macchiaioli.

While with Micheli, Modigliani studied not only landscape, but also portraiture, still life, and the nude. His fellow students recall that the last was where he displayed his greatest talent, and apparently this was not an entirely academic pursuit for the teenager: when not painting nudes, he was occupied with seducing the household maid.

Despite his rejection of the Macchiaioli approach, Modigliani nonetheless found favor with his teacher, who referred to him as "Superman", a pet name reflecting the fact that Modigliani was not only quite adept at his art, but also that he regularly quoted from Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Fattori himself would often visit the studio, and approved of the young artist's innovations.

In 1902, Modigliani continued what was to be a lifelong infatuation with life drawing, enrolling in the Accademia di Belle Arti (Scuola Libera di Nudo, or "Free School of Nude Studies") in Florence. A year later while still suffering from tuberculosis, he moved to Venice, where he registered to study at the Istituto di Belle Arti.

It is in Venice that he first smoked hashish and, rather than studying, began to spend time frequenting disreputable parts of the city. The impact of these lifestyle choices upon his developing artistic style is open to conjecture, although these choices do seem to be more than simple teenage rebellion, or the hedonism and bohemianism that was almost expected of artists of the time; his pursuit of the seedier side of life appears to have roots in his appreciation of radical philosophies, including those of Nietzsche.

Having been exposed to erudite philosophical literature as a young boy under the tutelage of Isaco Garsin, his maternal grandfather, he continued to read and be influenced through his art studies by the writings of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, Comte de Lautréamont, and others, and developed the belief that the only route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.

Letters that he wrote from his 'sabbatical' in Capri in 1901 clearly indicate that he is being more and more influenced by the thinking of Nietzsche The work of Lautréamont was equally influential at this time. This doomed poet's Les Chants de Maldoror became the seminal work for the Parisian Surrealists of Modigliani's generation, and the book became Modigliani's favorite to the extent that he learnt it by heart.The poetry of Lautréamont is characterized by the juxtaposition of fantastical elements, and by sadistic imagery; the fact that Modigliani was so taken by this text in his early teens gives a good indication of his developing tastes. Baudelaire and D'Annunzio similarly appealed to the young artist, with their interest in corrupted beauty, and the expression of that insight through Symbolist imagery.

Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia extensively from Capri, where his mother had taken him to assist in his recovery from tuberculosis. These letters are a sounding board for the developing ideas brewing in Modigliani's mind.

Ghiglia was seven years Modigliani's senior, and it is likely that it was he who showed the young man the limits of his horizons in Livorno. Like all precocious teenagers, Modigliani preferred the company of older companions, and Ghiglia's role in his adolescence was to be a sympathetic ear as he worked himself out, principally in the convoluted letters that he regularly sent, and which survive today.

“Dear friend, I write to pour myself out to you and to affirm myself to myself. I am the prey of great powers that surge forth and then disintegrate...A bourgeois told me today – insulted me – that I or at least my brain was lazy. It did me good. I should like such a warning every morning upon awakening: but they cannot understand us nor can they understand life...”

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, then the focal point of the avant-garde. In fact, his arrival at the centre of artistic experimentation coincided with the arrival of two other foreigners who were also to leave their marks upon the art world: Gino Severini and Juan Gris.

He settled in Le Bateau-Lavoir, a commune for penniless artists in Montmartre, renting himself a studio in Rue Caulaincourt. Even though this artists' quarter of Montmartre was characterized by generalized poverty, Modigliani himself presented — initially, at least — as one would expect the son of a family trying to maintain the appearances of its lost financial standing to present: his wardrobe was dapper without ostentation, and the studio he rented was appointed in a style appropriate to someone with a finely attuned taste in plush drapery and Renaissance reproductions.

He soon made efforts to assume the guise of the bohemian artist, but, even in his brown corduroys, scarlet scarf and large black hat, he continued to appear as if he were slumming it, having fallen upon harder times.

When he first arrived in Paris, he wrote home regularly to his mother, he sketched his nudes at the Académie Colarossi, and he drank wine in moderation. He was at that time considered by those who knew him as a bit reserved, verging on the asocial. He is noted to have commented, upon meeting Picasso who, at the time, was wearing his trademark workmen's clothes, that even though the man was a genius that did not excuse his uncouth appearance.

Within a year of arriving in Paris, however, his demeanour and reputation had changed dramatically. He transformed himself from a dapper academician artist into a sort of prince of vagabonds.

The poet and journalist Louis Latourette, upon visiting the artist's previously well-appointed studio after his transformation, discovered the place in upheaval, the Renaissance reproductions discarded from the walls, the plush drapes in disarray. Modigliani was already an alcoholic and a drug addict by this time, and his studio reflected this. Modigliani's behavior at this time sheds some light upon his developing style as an artist, in that the studio had become almost a sacrificial effigy for all that he resented about the academic art that had marked his life and his training up to that point.

Not only did he remove all the trappings of his bourgeois heritage from his studio, but he also set about destroying practically all of his own early work. He explained this extraordinary course of actions to his astonished neighbors thus:

“Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois.”

The motivation for this violent rejection of his earlier self is the subject of considerable speculation. From the time of his arrival in Paris, Modigliani consciously crafted a charade persona for himself and cultivated his reputation of hopeless drunk and voracious drug user. His escalating intake of drugs and alcohol may have been a means by which Modigliani masked his tuberculosis from his acquaintances, few of whom knew of his condition. Tuberculosis — the leading cause of death in France by 1900 — was highly communicable, there was no cure, and those who had it were feared, ostracized, and pitied. Modigliani thrived on camaraderie and would not let himself be isolated as an invalid; he sought to suppress his coughing bouts and any other recognizable signs of the disease that was slowly consuming him. Modigliani used drink and drugs to self-medicate, to serve as palliatives to ease his physical pain, helping him to maintain a facade of vitality and allowing him to continue to create his art.

Modigliani's use of drink and drugs intensified from about 1914 onward. After years of remission and recurrence, this was the period in when the symptoms of his tuberculosis worsened, signaling that the disease had reached an advanced stage.

He sought the company of artists such as Utrillo and Soutine, seeking acceptance and validation for his work from his colleagues. Modigliani's behavior stood out even in these Bohemian surroundings: he carried on frequent affairs, drank heavily, and used absinthe and hashish. While drunk, he would sometimes strip himself naked at social gatherings. He became the epitome of the tragic artist, creating a posthumous legend almost as well known as that of Vincent van Gogh.

During his early years in Paris, Modigliani worked at a furious pace. He was constantly sketching, making as many as a hundred drawings a day. However, many of his works were lost — destroyed by him as inferior, left behind in his frequent changes of address, or given to girlfriends who did not keep them.

He was first influenced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but around 1907 he became fascinated with the work of Paul Cézanne. Eventually he developed his own unique style, one that cannot be adequately categorized with those of other artists.

He met the first serious love of his life, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, in 1910, when he was 26. They had studios in the same building, and although 21-year-old Anna was recently married, they began an affair. Anna was tall (as Modigliani was only 5 foot 5 inches) with dark hair (like Modigliani's), pale skin and grey-green eyes, she embodied Modigliani's aesthetic ideal and the pair became engrossed in each other. After a year, however, Anna returned to her husband.

In 1909, Modigliani returned home to Livorno, sickly and tired from his wild lifestyle. Soon he was back in Paris, this time renting a studio in Montparnasse. He originally saw himself as a sculptor rather than a painter, and was encouraged to continue after Paul Guillaume, an ambitious young art dealer, took an interest in his work and introduced him to sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi. He was Constantin Brâncuşi's disciple for one year.

Although a series of Modigliani's sculptures were exhibited in the Salon d'Automne of 1912, by 1914 he abandoned sculpting and focused solely on his painting, a move precipitated by the difficulty in acquiring sculptural materials due to the outbreak of war, and by Modigliani's physical debilitation.

Modigliani painted a series of portraits of contemporary artists and friends in Montparnasse: Chaim Soutine, Moise Kisling, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Marie "Marevna" Vorobyev-Stebeslka, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, and Jean Cocteau, all sat for stylized renditions.

At the outset of World War I, Modigliani tried to enlist in the army but was refused because of his poor health.

Known as Modì, which translates as 'cursed' (maudit), by many Parisians, but as Dedo to his family and friends, Modigliani was a handsome man, and attracted much female attention. Women came and went until Beatrice Hastings entered his life. She stayed with him for almost two years, was the subject for several of his portraits.

In 1916, Modigliani befriended the Polish poet and art dealer Leopold Zborowski and his wife Anna. Zborowski became Modigliani's primary art dealer and friend during the artist's final years, helping him financially, and also organizing his show in Paris in 1917.

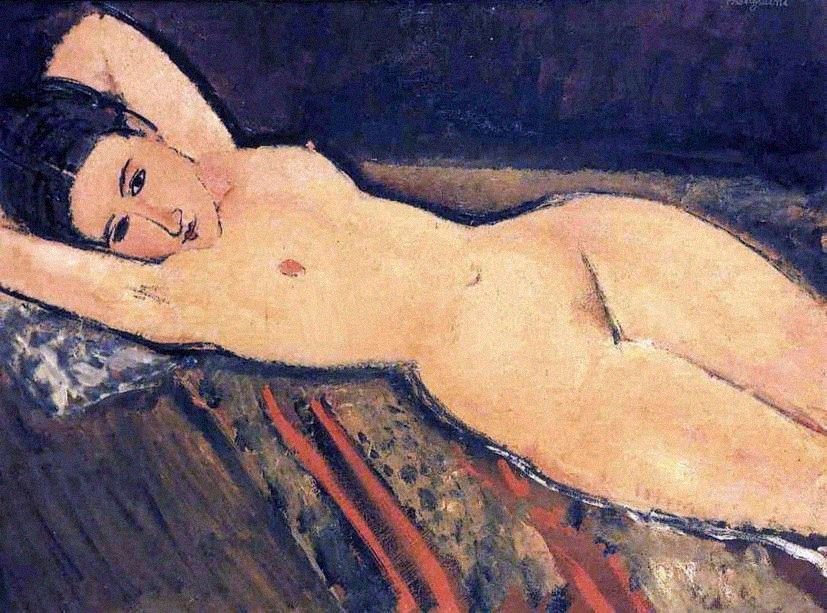

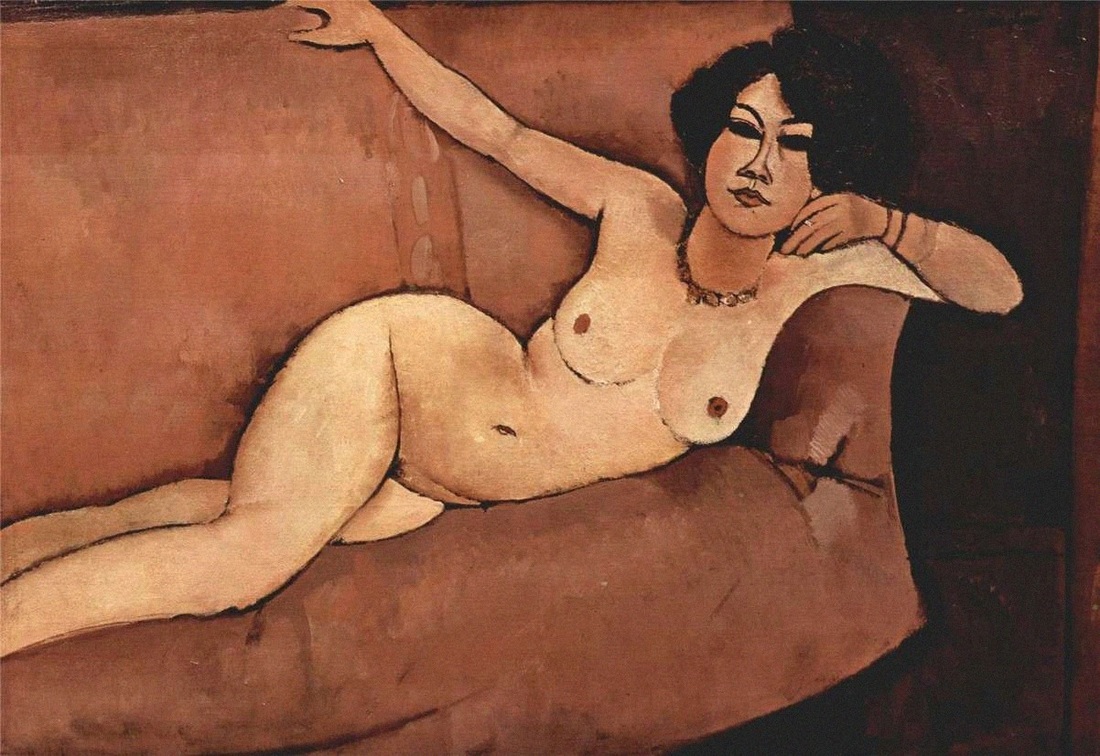

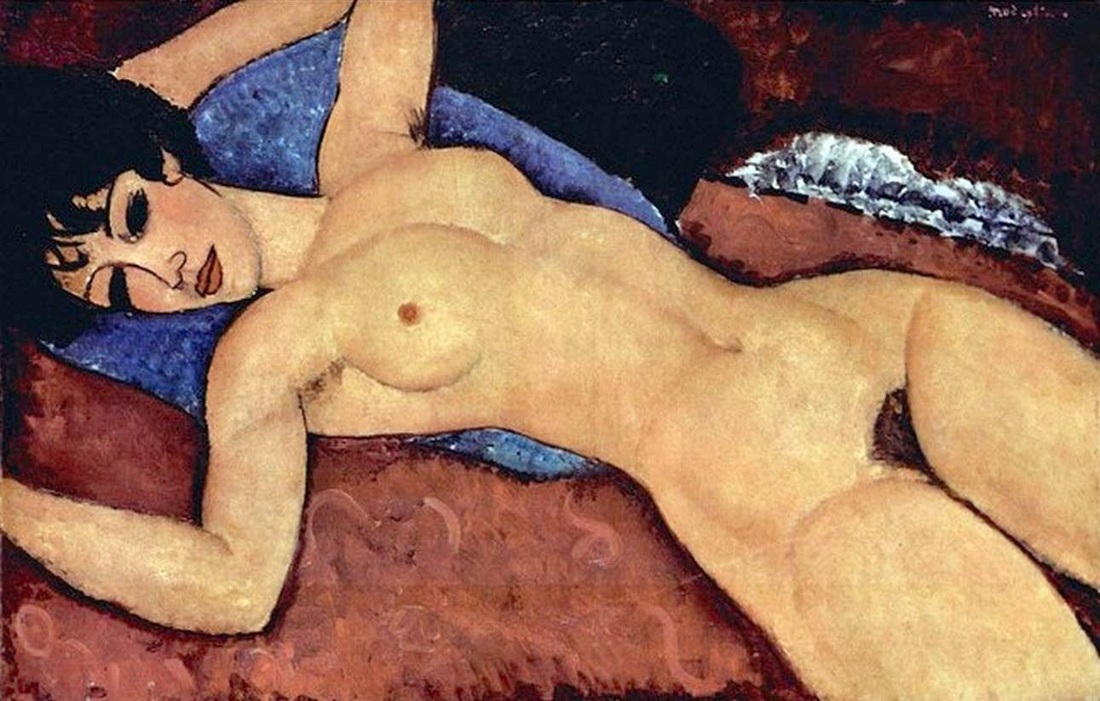

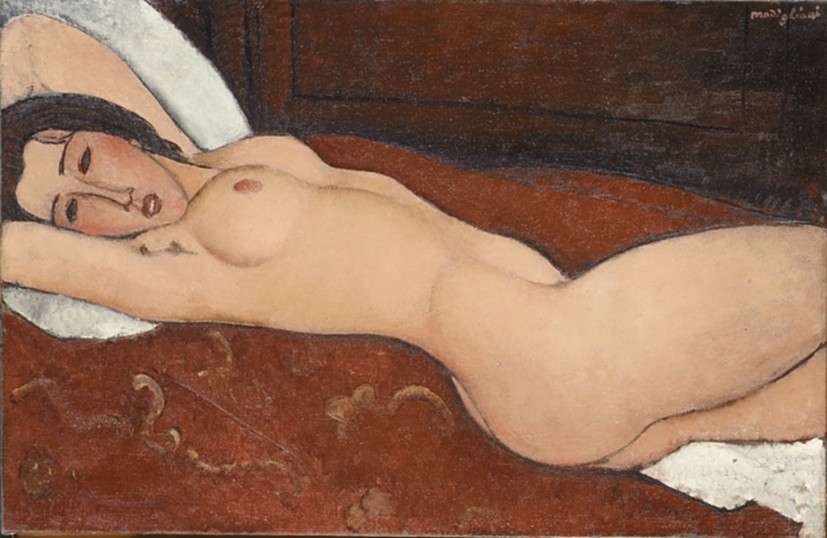

The several dozen nudes Modigliani painted between 1916 and 1919 constitute many of his best-known works. This series of nudes was commissioned by Modigliani's dealer and friend Leopold Zborowski, who lent the artist use of his apartment, supplied models and painting materials, and paid him between fifteen and twenty francs each day for his work.

The paintings from this arrangement were thus different from his previous depictions of friends and lovers in that they were funded by Zborowski either for his own collection, as a favor to his friend, or with an eye to their "commercial potential", rather than originating from the artist's personal circle of acquaintances.

The Paris show of 1917 was Modigliani's only solo exhibition during his life, and is "notorious" in modern art history for its sensational public reception and the attendant issues of obscenity. The show was closed by police on its opening day, but continued thereafter, most likely after the removal of paintings from the gallery's street front window.

In the spring of 1917, the Russian sculptor Chana Orloff introduced him to a beautiful 19-year-old art student named Jeanne Hébuterne. From a conservative bourgeois background, Hébuterne was renounced by her devout Roman Catholic family for her liaison with the painter, whom they saw as little more than a debauched derelict. Despite her family's objections, soon they were living together, and although Hébuterne was the current love of his life, their public scenes became more renowned than Modigliani's individual drunken exhibitions.

After he and Hébuterne moved to Nice, she became pregnant, and on November 29, 1918, gave birth to a daughter whom they named Jeanne.

Although he continued to paint, Modigliani's health was deteriorating rapidly, and his alcohol-induced blackouts became more frequent. In 1920, after not hearing from him for several days, his downstairs neighbor checked on the family and found Modigliani in bed delirious and holding onto Hébuterne, who was nearly nine months pregnant. They summoned a doctor, but little could be done because Modigliani was in the final stage of his disease, dying of tubercular meningitis.

Modigliani died on January 24, 1920. There was an enormous funeral, attended by many from the artistic communities in Montmartre and Montparnasse.

Hébuterne was taken to her parents' home, where, inconsolable, she threw herself out of a fifth-floor window, a day after Modigliani's death, killing herself and her unborn child. Modigliani was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hébuterne was buried at the Cimetière de Bagneux near Paris, and it was not until 1930 that her embittered family allowed her body to be moved to rest beside Modigliani. A single tombstone honors them both.

His epitaph reads:

"Struck down by Death at the moment of glory."

Hers reads:

"Devoted companion to the extreme sacrifice."

Modigliani was born into a Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for those persecuted for their religion, and was home to a large Jewish community. His maternal great-great-grandfather, Solomon Garsin, had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century as a refugee.

Modigliani's mother (Eugénie Garsin) who was born and grew up in Marseille, was descended from an intellectual, scholarly family of Sephardic Jews, generations of whom had resided along the Mediterranean coastline. Her ancestors were learned people, fluent in many languages, known authorities on sacred Jewish texts and founders of a school of Talmudic studies. Family legend traced the Garsins' lineage to the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

The family business was believed to be a credit agency with branches in Livorno, Marseille, Tunis, and London. Their financial fortunes ebbed and flowed. At times they enjoyed affluence, at other times they were subject to dire financial crises and reduced circumstances.

Modigliani’s father, Flaminio, hailed from a family of successful businessmen and entrepreneurs. While not as culturally sophisticated as the Garsins, they knew how to invest into and develop thriving business endeavors. Their wealth was derived from mining the metals abundant in the area of Sardinia and Tuscany and extracting and exporting the ores. When the Garsin and Modigliani families announced the engagement of their children, Flaminio was a wealthy young mining engineer. He managed the mine in Sardinia and oversaw the almost 30,000 acres of timberland the family owned. He also was expert in both forestry and farming management. A reversal in fortune occurred to this prosperous family in 1883. An economic downturn in the price of metal plunged the Modiglianis into bankruptcy. Ever resourceful, Modigliani’s mother used her social contacts to establish a school and, along with her two sisters, made the school into a successful enterprise.

Modigliani was the fourth child, whose birth coincided with the disastrous financial collapse of his father's business interests. Amedeo's birth saved the family from ruin; according to an ancient law, creditors could not seize the bed of a pregnant woman or a mother with a newborn child. The bailiffs entered the family's home just as Eugenia went into labor; the family protected their most valuable assets by piling them on top of her.

Modigliani had a close relationship with his mother, who taught him at home until he was 10. Beset with health problems after an attack of pleurisy when he was about 11, a few years later he developed a case of typhoid fever. When he was 16 he was taken ill again and contracted the tuberculosis which would later claim his life. After Modigliani recovered from the second bout of pleurisy, his mother took him on a tour of southern Italy: Naples, Capri, Rome and Amalfi, then north to Florence and Venice.

Modigliani worked in Micheli's Art School from 1898 to 1900. Here his earliest formal artistic instruction took place in an atmosphere steeped in a study of the styles and themes of 19th-century Italian art. In his earliest Parisian work, traces of this influence, and that of his studies of Renaissance art, can still be seen. His nascent work was shaped as much by such artists as Giovanni Boldini as by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Modigliani showed great promise while with Micheli, and ceased his studies only when he was forced to, by the onset of tuberculosis.

In 1901, whilst in Rome, Modigliani admired the work of Domenico Morelli, a painter of melodramatic religious and literary scenes. Morelli had served as an inspiration for a group of iconoclasts who were known by the title "the Macchiaioli" (from macchia —"dash of colour", or, more derogatively, "stain"), and Modigliani had already been exposed to the influences of the Macchiaioli.

This localized landscape movement reacted against the bourgeois styling of the academic genre painters. While sympathetically connected to (and actually pre-dating) the French Impressionists, the Macchiaioli did not make the same impact upon international art culture as did the contemporaries and followers of Monet, and are today largely forgotten outside of Italy.

Modigliani's connection with the movement was through Guglielmo Micheli, his first art teacher. Micheli was not only a Macchiaiolo himself, but had been a pupil of the famous Giovanni Fattori, a founder of the movement. Micheli's work, however, was so fashionable and the genre so commonplace that the young Modigliani reacted against it, preferring to ignore the obsession with landscape that, as with French Impressionism, characterized the movement. Micheli also tried to encourage his pupils to paint en plein air, but Modigliani never really got a taste for this style of working, sketching in cafés, but preferring to paint indoors, and especially in his own studio. Even when compelled to paint landscapes (three are known to exist), Modigliani chose a proto-Cubist palette more akin to Cézanne than to the Macchiaioli.

While with Micheli, Modigliani studied not only landscape, but also portraiture, still life, and the nude. His fellow students recall that the last was where he displayed his greatest talent, and apparently this was not an entirely academic pursuit for the teenager: when not painting nudes, he was occupied with seducing the household maid.

Despite his rejection of the Macchiaioli approach, Modigliani nonetheless found favor with his teacher, who referred to him as "Superman", a pet name reflecting the fact that Modigliani was not only quite adept at his art, but also that he regularly quoted from Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Fattori himself would often visit the studio, and approved of the young artist's innovations.

In 1902, Modigliani continued what was to be a lifelong infatuation with life drawing, enrolling in the Accademia di Belle Arti (Scuola Libera di Nudo, or "Free School of Nude Studies") in Florence. A year later while still suffering from tuberculosis, he moved to Venice, where he registered to study at the Istituto di Belle Arti.

It is in Venice that he first smoked hashish and, rather than studying, began to spend time frequenting disreputable parts of the city. The impact of these lifestyle choices upon his developing artistic style is open to conjecture, although these choices do seem to be more than simple teenage rebellion, or the hedonism and bohemianism that was almost expected of artists of the time; his pursuit of the seedier side of life appears to have roots in his appreciation of radical philosophies, including those of Nietzsche.

Having been exposed to erudite philosophical literature as a young boy under the tutelage of Isaco Garsin, his maternal grandfather, he continued to read and be influenced through his art studies by the writings of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, Comte de Lautréamont, and others, and developed the belief that the only route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.

Letters that he wrote from his 'sabbatical' in Capri in 1901 clearly indicate that he is being more and more influenced by the thinking of Nietzsche The work of Lautréamont was equally influential at this time. This doomed poet's Les Chants de Maldoror became the seminal work for the Parisian Surrealists of Modigliani's generation, and the book became Modigliani's favorite to the extent that he learnt it by heart.The poetry of Lautréamont is characterized by the juxtaposition of fantastical elements, and by sadistic imagery; the fact that Modigliani was so taken by this text in his early teens gives a good indication of his developing tastes. Baudelaire and D'Annunzio similarly appealed to the young artist, with their interest in corrupted beauty, and the expression of that insight through Symbolist imagery.

Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia extensively from Capri, where his mother had taken him to assist in his recovery from tuberculosis. These letters are a sounding board for the developing ideas brewing in Modigliani's mind.

Ghiglia was seven years Modigliani's senior, and it is likely that it was he who showed the young man the limits of his horizons in Livorno. Like all precocious teenagers, Modigliani preferred the company of older companions, and Ghiglia's role in his adolescence was to be a sympathetic ear as he worked himself out, principally in the convoluted letters that he regularly sent, and which survive today.

“Dear friend, I write to pour myself out to you and to affirm myself to myself. I am the prey of great powers that surge forth and then disintegrate...A bourgeois told me today – insulted me – that I or at least my brain was lazy. It did me good. I should like such a warning every morning upon awakening: but they cannot understand us nor can they understand life...”

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, then the focal point of the avant-garde. In fact, his arrival at the centre of artistic experimentation coincided with the arrival of two other foreigners who were also to leave their marks upon the art world: Gino Severini and Juan Gris.

He settled in Le Bateau-Lavoir, a commune for penniless artists in Montmartre, renting himself a studio in Rue Caulaincourt. Even though this artists' quarter of Montmartre was characterized by generalized poverty, Modigliani himself presented — initially, at least — as one would expect the son of a family trying to maintain the appearances of its lost financial standing to present: his wardrobe was dapper without ostentation, and the studio he rented was appointed in a style appropriate to someone with a finely attuned taste in plush drapery and Renaissance reproductions.

He soon made efforts to assume the guise of the bohemian artist, but, even in his brown corduroys, scarlet scarf and large black hat, he continued to appear as if he were slumming it, having fallen upon harder times.

When he first arrived in Paris, he wrote home regularly to his mother, he sketched his nudes at the Académie Colarossi, and he drank wine in moderation. He was at that time considered by those who knew him as a bit reserved, verging on the asocial. He is noted to have commented, upon meeting Picasso who, at the time, was wearing his trademark workmen's clothes, that even though the man was a genius that did not excuse his uncouth appearance.

Within a year of arriving in Paris, however, his demeanour and reputation had changed dramatically. He transformed himself from a dapper academician artist into a sort of prince of vagabonds.

The poet and journalist Louis Latourette, upon visiting the artist's previously well-appointed studio after his transformation, discovered the place in upheaval, the Renaissance reproductions discarded from the walls, the plush drapes in disarray. Modigliani was already an alcoholic and a drug addict by this time, and his studio reflected this. Modigliani's behavior at this time sheds some light upon his developing style as an artist, in that the studio had become almost a sacrificial effigy for all that he resented about the academic art that had marked his life and his training up to that point.

Not only did he remove all the trappings of his bourgeois heritage from his studio, but he also set about destroying practically all of his own early work. He explained this extraordinary course of actions to his astonished neighbors thus:

“Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois.”

The motivation for this violent rejection of his earlier self is the subject of considerable speculation. From the time of his arrival in Paris, Modigliani consciously crafted a charade persona for himself and cultivated his reputation of hopeless drunk and voracious drug user. His escalating intake of drugs and alcohol may have been a means by which Modigliani masked his tuberculosis from his acquaintances, few of whom knew of his condition. Tuberculosis — the leading cause of death in France by 1900 — was highly communicable, there was no cure, and those who had it were feared, ostracized, and pitied. Modigliani thrived on camaraderie and would not let himself be isolated as an invalid; he sought to suppress his coughing bouts and any other recognizable signs of the disease that was slowly consuming him. Modigliani used drink and drugs to self-medicate, to serve as palliatives to ease his physical pain, helping him to maintain a facade of vitality and allowing him to continue to create his art.

Modigliani's use of drink and drugs intensified from about 1914 onward. After years of remission and recurrence, this was the period in when the symptoms of his tuberculosis worsened, signaling that the disease had reached an advanced stage.

He sought the company of artists such as Utrillo and Soutine, seeking acceptance and validation for his work from his colleagues. Modigliani's behavior stood out even in these Bohemian surroundings: he carried on frequent affairs, drank heavily, and used absinthe and hashish. While drunk, he would sometimes strip himself naked at social gatherings. He became the epitome of the tragic artist, creating a posthumous legend almost as well known as that of Vincent van Gogh.

During his early years in Paris, Modigliani worked at a furious pace. He was constantly sketching, making as many as a hundred drawings a day. However, many of his works were lost — destroyed by him as inferior, left behind in his frequent changes of address, or given to girlfriends who did not keep them.

He was first influenced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but around 1907 he became fascinated with the work of Paul Cézanne. Eventually he developed his own unique style, one that cannot be adequately categorized with those of other artists.

He met the first serious love of his life, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, in 1910, when he was 26. They had studios in the same building, and although 21-year-old Anna was recently married, they began an affair. Anna was tall (as Modigliani was only 5 foot 5 inches) with dark hair (like Modigliani's), pale skin and grey-green eyes, she embodied Modigliani's aesthetic ideal and the pair became engrossed in each other. After a year, however, Anna returned to her husband.

In 1909, Modigliani returned home to Livorno, sickly and tired from his wild lifestyle. Soon he was back in Paris, this time renting a studio in Montparnasse. He originally saw himself as a sculptor rather than a painter, and was encouraged to continue after Paul Guillaume, an ambitious young art dealer, took an interest in his work and introduced him to sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi. He was Constantin Brâncuşi's disciple for one year.

Although a series of Modigliani's sculptures were exhibited in the Salon d'Automne of 1912, by 1914 he abandoned sculpting and focused solely on his painting, a move precipitated by the difficulty in acquiring sculptural materials due to the outbreak of war, and by Modigliani's physical debilitation.

Modigliani painted a series of portraits of contemporary artists and friends in Montparnasse: Chaim Soutine, Moise Kisling, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Marie "Marevna" Vorobyev-Stebeslka, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, and Jean Cocteau, all sat for stylized renditions.

At the outset of World War I, Modigliani tried to enlist in the army but was refused because of his poor health.

Known as Modì, which translates as 'cursed' (maudit), by many Parisians, but as Dedo to his family and friends, Modigliani was a handsome man, and attracted much female attention. Women came and went until Beatrice Hastings entered his life. She stayed with him for almost two years, was the subject for several of his portraits.

In 1916, Modigliani befriended the Polish poet and art dealer Leopold Zborowski and his wife Anna. Zborowski became Modigliani's primary art dealer and friend during the artist's final years, helping him financially, and also organizing his show in Paris in 1917.

The several dozen nudes Modigliani painted between 1916 and 1919 constitute many of his best-known works. This series of nudes was commissioned by Modigliani's dealer and friend Leopold Zborowski, who lent the artist use of his apartment, supplied models and painting materials, and paid him between fifteen and twenty francs each day for his work.

The paintings from this arrangement were thus different from his previous depictions of friends and lovers in that they were funded by Zborowski either for his own collection, as a favor to his friend, or with an eye to their "commercial potential", rather than originating from the artist's personal circle of acquaintances.

The Paris show of 1917 was Modigliani's only solo exhibition during his life, and is "notorious" in modern art history for its sensational public reception and the attendant issues of obscenity. The show was closed by police on its opening day, but continued thereafter, most likely after the removal of paintings from the gallery's street front window.

In the spring of 1917, the Russian sculptor Chana Orloff introduced him to a beautiful 19-year-old art student named Jeanne Hébuterne. From a conservative bourgeois background, Hébuterne was renounced by her devout Roman Catholic family for her liaison with the painter, whom they saw as little more than a debauched derelict. Despite her family's objections, soon they were living together, and although Hébuterne was the current love of his life, their public scenes became more renowned than Modigliani's individual drunken exhibitions.

After he and Hébuterne moved to Nice, she became pregnant, and on November 29, 1918, gave birth to a daughter whom they named Jeanne.

Although he continued to paint, Modigliani's health was deteriorating rapidly, and his alcohol-induced blackouts became more frequent. In 1920, after not hearing from him for several days, his downstairs neighbor checked on the family and found Modigliani in bed delirious and holding onto Hébuterne, who was nearly nine months pregnant. They summoned a doctor, but little could be done because Modigliani was in the final stage of his disease, dying of tubercular meningitis.

Modigliani died on January 24, 1920. There was an enormous funeral, attended by many from the artistic communities in Montmartre and Montparnasse.

Hébuterne was taken to her parents' home, where, inconsolable, she threw herself out of a fifth-floor window, a day after Modigliani's death, killing herself and her unborn child. Modigliani was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hébuterne was buried at the Cimetière de Bagneux near Paris, and it was not until 1930 that her embittered family allowed her body to be moved to rest beside Modigliani. A single tombstone honors them both.

His epitaph reads:

"Struck down by Death at the moment of glory."

Hers reads:

"Devoted companion to the extreme sacrifice."

Le violoncelliste (The cellist)

1909, oil on canvas, 131 x 81cm, Private Collection

Executed in 1909, Le violoncelliste is the finest achievement of Modigliani's early career. Exquisitely composed, it represents the culmination of a period in Modigliani's art that was characterized by the influence of Cezanne.

In the present work, Modigliani incorporates the lessons that he has learned from Cezanne and ultimately transcends them by resolving Cezanne's tonal harmonies and formal relationships into a more fluid and deliberately sculptural composition. When exhibited at the Salon des Indpendants in 1910, Le violoncelliste was famously acclaimed by Modigliani's friend and patron Dr. Paul Alexandre as being "better than Cezanne."

In addition to being Modigliani's ultimate statement on Cezanne, Le violoncelliste also marks the dawning in Modigliani's art of the artist's lifelong fascination with sculpture and in particular the influence of Brancusi. On his arrival in Paris in 1906, Modigliani had introduced himself around town as primarily a sculptor and shortly before he began work on Le violoncelliste in 1909, he had asked Dr. Paul Alexandre to introduce him to the famous Romanian sculptor. A long-time admirer of Brancusi's work, over the ensuing months the Romanian became both a significant influence on Modigliani's work and a close friend and substitute father-figure for the young Italian artist.

Brancusi was a shy man who seldom agreed to be photographed or painted, yet on the reverse of the oil study for Le violoncelliste there appears a rare portrait of Brancusi by Modigliani that remained unfinished. Many of the features of this portrait resemble those of Le violoncelliste and indeed it has been suggested that it is also a portrait of Brancusi, who though not known to have played the cello was a keen violinist and played regularly with the celebrated naive painter, Henri Rousseau. Despite the facial resemblance, the slender body and elongated forms of the figure in the painting are inconsistent with Brancusi's more robust figure.

The influence of Brancusi's elegant sculptural simplification of form on Modigliani during this period is nevertheless undeniable and can be most clearly witnessed in the smooth rounded and somewhat exaggerated forms of the cellist's features and in the carefully orchestrated spatial depth of the composition. Le violoncelliste was painted concurrently with a number of very sculptural paintings and drawings which, taking their inspiration from Brancusi and Cubism, attempt to convey three-dimensional form in two dimensions by means of highly stylized distortion.

Although Le violoncelliste is executed very much in the Cezanne-influenced style of his early work, it is not only Modigliani's earliest masterpiece but also the first of his paintings to clearly display the direction and character of the artist's later work.

1909, oil on canvas, 131 x 81cm, Private Collection

Executed in 1909, Le violoncelliste is the finest achievement of Modigliani's early career. Exquisitely composed, it represents the culmination of a period in Modigliani's art that was characterized by the influence of Cezanne.

In the present work, Modigliani incorporates the lessons that he has learned from Cezanne and ultimately transcends them by resolving Cezanne's tonal harmonies and formal relationships into a more fluid and deliberately sculptural composition. When exhibited at the Salon des Indpendants in 1910, Le violoncelliste was famously acclaimed by Modigliani's friend and patron Dr. Paul Alexandre as being "better than Cezanne."

In addition to being Modigliani's ultimate statement on Cezanne, Le violoncelliste also marks the dawning in Modigliani's art of the artist's lifelong fascination with sculpture and in particular the influence of Brancusi. On his arrival in Paris in 1906, Modigliani had introduced himself around town as primarily a sculptor and shortly before he began work on Le violoncelliste in 1909, he had asked Dr. Paul Alexandre to introduce him to the famous Romanian sculptor. A long-time admirer of Brancusi's work, over the ensuing months the Romanian became both a significant influence on Modigliani's work and a close friend and substitute father-figure for the young Italian artist.

Brancusi was a shy man who seldom agreed to be photographed or painted, yet on the reverse of the oil study for Le violoncelliste there appears a rare portrait of Brancusi by Modigliani that remained unfinished. Many of the features of this portrait resemble those of Le violoncelliste and indeed it has been suggested that it is also a portrait of Brancusi, who though not known to have played the cello was a keen violinist and played regularly with the celebrated naive painter, Henri Rousseau. Despite the facial resemblance, the slender body and elongated forms of the figure in the painting are inconsistent with Brancusi's more robust figure.

The influence of Brancusi's elegant sculptural simplification of form on Modigliani during this period is nevertheless undeniable and can be most clearly witnessed in the smooth rounded and somewhat exaggerated forms of the cellist's features and in the carefully orchestrated spatial depth of the composition. Le violoncelliste was painted concurrently with a number of very sculptural paintings and drawings which, taking their inspiration from Brancusi and Cubism, attempt to convey three-dimensional form in two dimensions by means of highly stylized distortion.

Although Le violoncelliste is executed very much in the Cezanne-influenced style of his early work, it is not only Modigliani's earliest masterpiece but also the first of his paintings to clearly display the direction and character of the artist's later work.

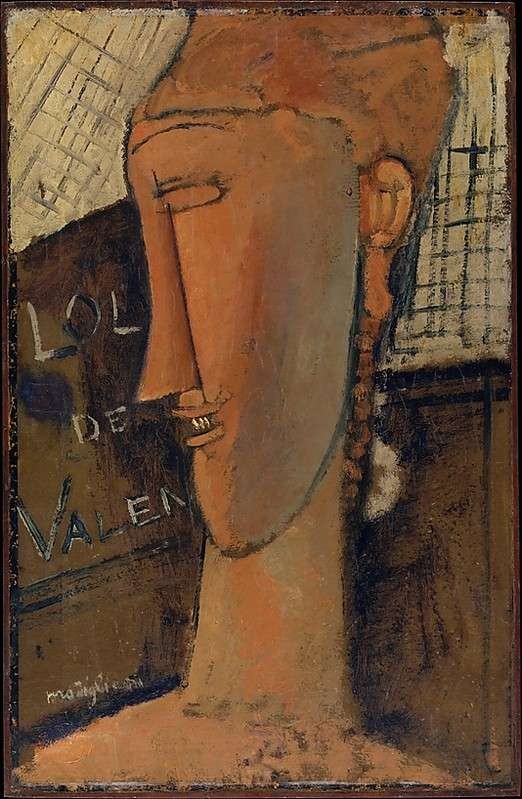

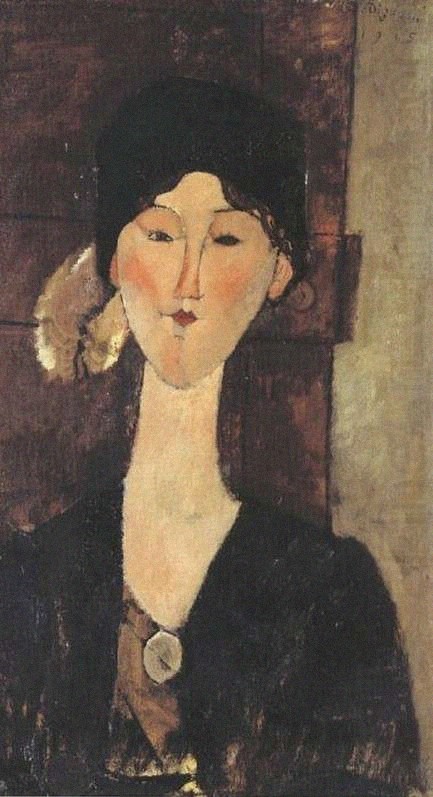

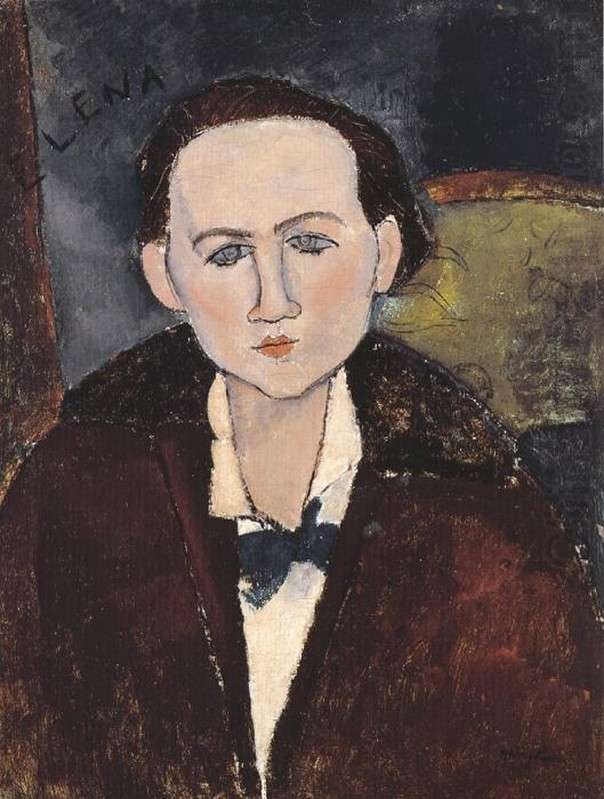

Lola de Valence

1915, Oil on paper, mounted on wood, 50.8 x 33.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lola de Valence was widely known as a dancer and one-time Manet model. The sitter's stylized coiffure and facial features still reflect Modigliani's early, simplified sculptures. The muted palette and nondescript setting reveal the artist's cautious beginnings with painting.

1915, Oil on paper, mounted on wood, 50.8 x 33.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lola de Valence was widely known as a dancer and one-time Manet model. The sitter's stylized coiffure and facial features still reflect Modigliani's early, simplified sculptures. The muted palette and nondescript setting reveal the artist's cautious beginnings with painting.

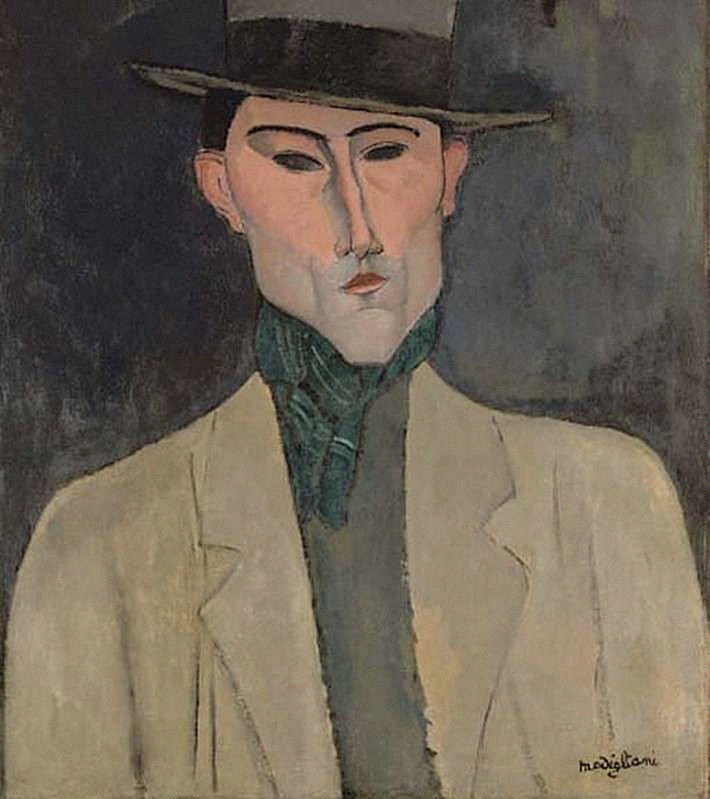

Homme au chapeau (Man with hat)

1915, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Private Collection

For Modigliani, sculpture had been a vocation, and yet his health meant that he was physically unable to withstand the level of exertion that work in stone - the only sculptural medium that he truly believed in - demanded from him. He returned, then, to painting, but his experiences as a sculptor came to flavor his work, giving them their unique sense of modeling - a factor that is so vividly evident in the face of the Homme au chapeau. These characteristics would come to result in the increasing sense of accomplishment and therefore the consequent popularity of his pictures from the period.

Modigliani's portraits often introduce this sculptural sense of the three-dimensional to the face, but deliberately suppress it in the rest of the painting. In Homme au chapeau, this is clear both in the dark background and also in the clothes that he is wearing. This flatness contrasts heavily with the finely modeled face, an effect that is heightened by the difference that exists even in terms of the textures of the paint in the various areas. Where the lines of the jacket are marked with simplicity, those of the face have been carefully applied with an acute appreciation of the modulation of tone. This is especially evident in the depiction of the subject's nose, where thin, sharp lines have been used to evoke perfectly the shape and form. In addition, the deft manipulation of shade, in the lower half of the face, shows us that the sitter's face is inclined and somewhat unshaven.

1915, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Private Collection

For Modigliani, sculpture had been a vocation, and yet his health meant that he was physically unable to withstand the level of exertion that work in stone - the only sculptural medium that he truly believed in - demanded from him. He returned, then, to painting, but his experiences as a sculptor came to flavor his work, giving them their unique sense of modeling - a factor that is so vividly evident in the face of the Homme au chapeau. These characteristics would come to result in the increasing sense of accomplishment and therefore the consequent popularity of his pictures from the period.

Modigliani's portraits often introduce this sculptural sense of the three-dimensional to the face, but deliberately suppress it in the rest of the painting. In Homme au chapeau, this is clear both in the dark background and also in the clothes that he is wearing. This flatness contrasts heavily with the finely modeled face, an effect that is heightened by the difference that exists even in terms of the textures of the paint in the various areas. Where the lines of the jacket are marked with simplicity, those of the face have been carefully applied with an acute appreciation of the modulation of tone. This is especially evident in the depiction of the subject's nose, where thin, sharp lines have been used to evoke perfectly the shape and form. In addition, the deft manipulation of shade, in the lower half of the face, shows us that the sitter's face is inclined and somewhat unshaven.

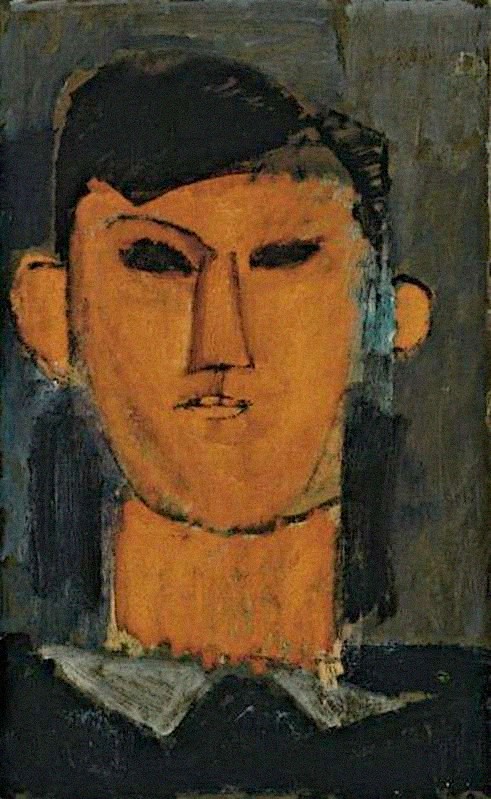

Portrait de Picasso

1915, oil on paper laid down on card, canvas backed, 34.2 x 26.3cm, Private Collection

Picasso and Modigliani both had a great respect for each other's artistic abilities, Modigliani referred to Picasso as "always being ten years ahead of the rest of us”. This portrait of Picasso is one of a series of portraits of his fellow artists Modigliani painted in 1915. Following the 1914 portraits of F. B. Haviland and Diego Rivera in 1915.

By this time Montparnasse had been discovered by artists from all parts of the world. It had superseded Montmartre as the centre for intellectual life. The Closerie des Lilas, as well as the two famous cafés, La Rotonde and Le Dôme, were the meeting places for painters and poets who often engaged in heated discussion with political exiles such as Trotsky. Artists returning from the front could find their friends in those café terraces. Writing about the atmosphere, Roland Penrose recalled, "The company was widely international, those in uniform such as Léger, Raynal, Braque, Derain, Apollinaire and many others mixed again with painters, sculptors and writers such as Modigliani, Kisling, Severini, Soffici, Chirico, Lipchitz, Archipenko, Brancusi, Cendrars, Reverdy, Salmon, Dalize. There was no lack of talent among them..." (Picasso: His Life and Work, London, 1958, p. 193).

1915, oil on paper laid down on card, canvas backed, 34.2 x 26.3cm, Private Collection

Picasso and Modigliani both had a great respect for each other's artistic abilities, Modigliani referred to Picasso as "always being ten years ahead of the rest of us”. This portrait of Picasso is one of a series of portraits of his fellow artists Modigliani painted in 1915. Following the 1914 portraits of F. B. Haviland and Diego Rivera in 1915.

By this time Montparnasse had been discovered by artists from all parts of the world. It had superseded Montmartre as the centre for intellectual life. The Closerie des Lilas, as well as the two famous cafés, La Rotonde and Le Dôme, were the meeting places for painters and poets who often engaged in heated discussion with political exiles such as Trotsky. Artists returning from the front could find their friends in those café terraces. Writing about the atmosphere, Roland Penrose recalled, "The company was widely international, those in uniform such as Léger, Raynal, Braque, Derain, Apollinaire and many others mixed again with painters, sculptors and writers such as Modigliani, Kisling, Severini, Soffici, Chirico, Lipchitz, Archipenko, Brancusi, Cendrars, Reverdy, Salmon, Dalize. There was no lack of talent among them..." (Picasso: His Life and Work, London, 1958, p. 193).

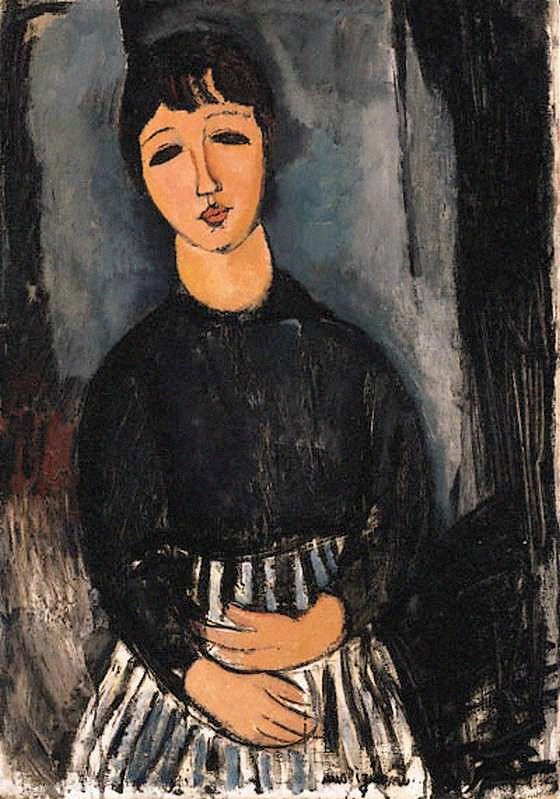

La servante au tablier ray (The servant in apron ray)

1916, oil on canvas, 92 x 64.8 cm, Private Collection

More than any other artist of the early twentieth century, Modigliani concentrated on portraiture as his principal medium of creativity. The present work, painted in 1916, is a masterpiece from Modigliani's first period of full artistic maturity.

Jacques Lipchitz, the sculptor, wrote a short book on Modigliani. An intimate friend of the painter, he commissioned Modigliani to do a wedding portrait of Lipchitz and his wife. He has left a fascinating account of Modigliani's working procedure: He preferred painting on a closely woven canvas, and sometimes when he had finished the work he placed a sheet of paper carefully over the fresh paint to merge the colors. He worked without an easel and with the minimum fuss, placing his canvas on a chair and painting quietly. From time to time he would get up and glance critically over his work and look at his models. According to Lipchitz, Modigliani charged 10 francs and a bottle of wine per sitting. Other artists and clients testify that Modigliani always drank as he worked. Lipchitz has written the best analysis of Modigliani's methods and style:

“His own art was an art of personal feeling. He worked furiously, dashing off drawing after drawing without stopping to correct and ponder. He worked, it seemed, entirely by instinct - which, however, was extremely fine and sensitive, perhaps owing much to his Italian inheritance and his love of the early Renaissance masters. He could not forget his interest in people, and he painted them, so to say, with abandon.”

1916, oil on canvas, 92 x 64.8 cm, Private Collection

More than any other artist of the early twentieth century, Modigliani concentrated on portraiture as his principal medium of creativity. The present work, painted in 1916, is a masterpiece from Modigliani's first period of full artistic maturity.

Jacques Lipchitz, the sculptor, wrote a short book on Modigliani. An intimate friend of the painter, he commissioned Modigliani to do a wedding portrait of Lipchitz and his wife. He has left a fascinating account of Modigliani's working procedure: He preferred painting on a closely woven canvas, and sometimes when he had finished the work he placed a sheet of paper carefully over the fresh paint to merge the colors. He worked without an easel and with the minimum fuss, placing his canvas on a chair and painting quietly. From time to time he would get up and glance critically over his work and look at his models. According to Lipchitz, Modigliani charged 10 francs and a bottle of wine per sitting. Other artists and clients testify that Modigliani always drank as he worked. Lipchitz has written the best analysis of Modigliani's methods and style:

“His own art was an art of personal feeling. He worked furiously, dashing off drawing after drawing without stopping to correct and ponder. He worked, it seemed, entirely by instinct - which, however, was extremely fine and sensitive, perhaps owing much to his Italian inheritance and his love of the early Renaissance masters. He could not forget his interest in people, and he painted them, so to say, with abandon.”

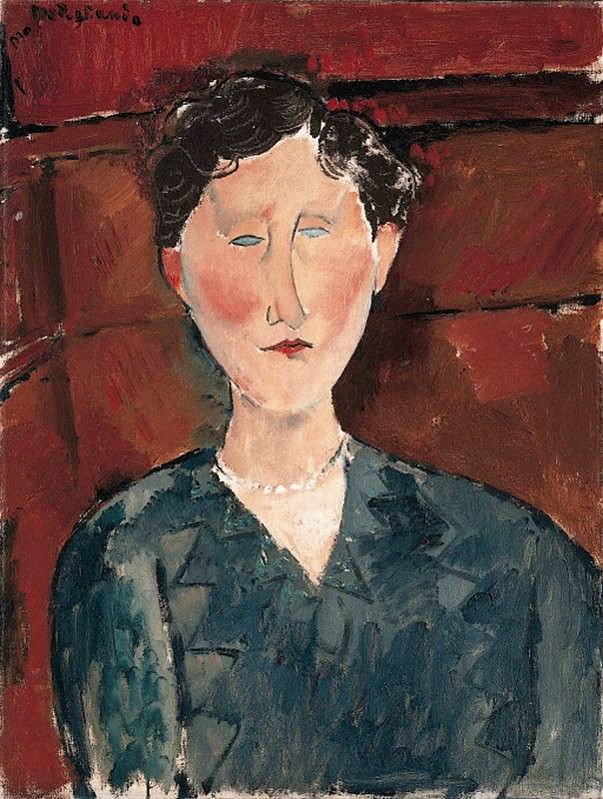

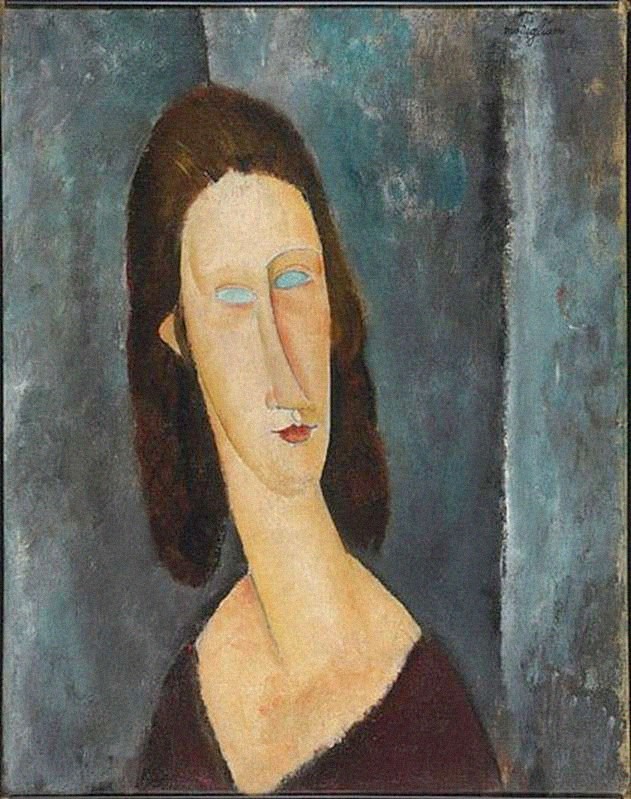

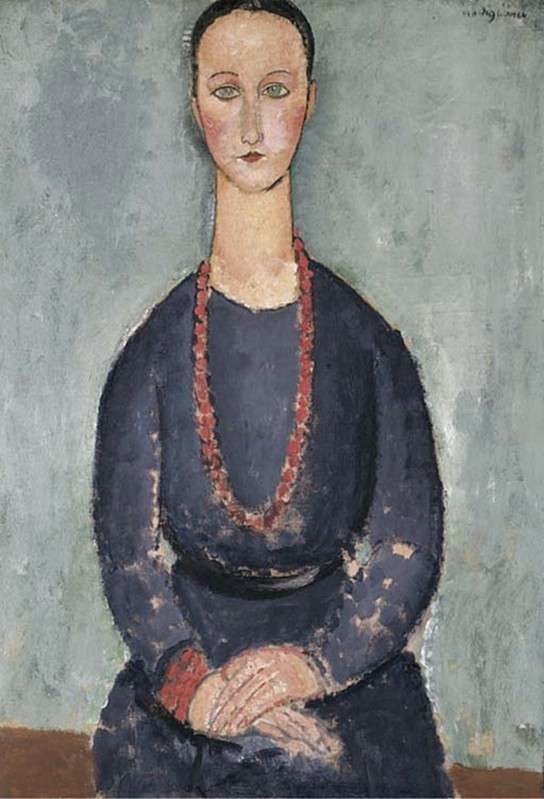

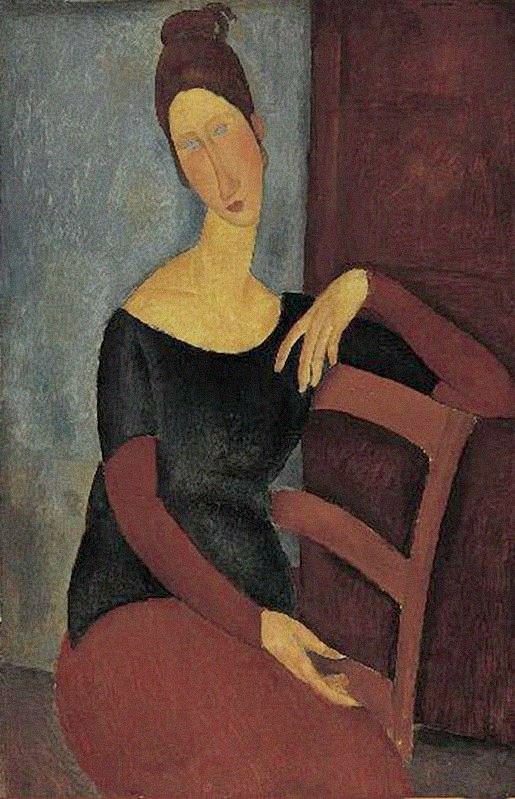

Portrait de femme au corsage bleu (Portrait of woman in blue blouse)

c. 1916, Oil on canvas, 61 x 45 cm, Private Collection

The strong sculptural elements seen in the rendering of this portrait are reminiscent of the artist's stone heads of 1911-1912 and more importantly, reflect his exploration of Cubism from the study of Picasso's early Cubist paintings. Picasso and Modigliani became friends soon after Modigliani's 1906 arrival in Paris. Picasso's portraits of his mistress Fernande Olivier executed during 1908-1909 depict her face as a series of fractured planes, and works such as these were influential in the development of Modigliani's own work. While Portrait de femme au corsage bleu exhibits a more naturalistic rendering of the face, Modigliani emphasized the temples and cheeks of the face to create a highly modulated surface.

The works of Paul Cézanne were another seminal influence in the artist's development. The present picture is strongly reminiscent of Cézanne's portraits of Madame Cézanne seated in front of a interior wall, such as Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune, 1888-1890. The composition of Portrait de femme au corsage bleu exhibits a similar treatment of the face, shown in asymmetrical features and brushstrokes of color defining the planes of the face.

Building on the influences of Picasso and Cézanne, Modigliani created a unique style of portraiture that utilizes a deeply hued palette, rich impasto, and linear drawing. While he incorporated external influences into his work, Modigliani based his portraits on keen observation of the sitter and their attributes. In the present work, the sitter's calm demeanor and tasteful wardrobe are clearly evident; however, the individualizing characteristics have been transformed and rendered immortal by the artist.

c. 1916, Oil on canvas, 61 x 45 cm, Private Collection

The strong sculptural elements seen in the rendering of this portrait are reminiscent of the artist's stone heads of 1911-1912 and more importantly, reflect his exploration of Cubism from the study of Picasso's early Cubist paintings. Picasso and Modigliani became friends soon after Modigliani's 1906 arrival in Paris. Picasso's portraits of his mistress Fernande Olivier executed during 1908-1909 depict her face as a series of fractured planes, and works such as these were influential in the development of Modigliani's own work. While Portrait de femme au corsage bleu exhibits a more naturalistic rendering of the face, Modigliani emphasized the temples and cheeks of the face to create a highly modulated surface.

The works of Paul Cézanne were another seminal influence in the artist's development. The present picture is strongly reminiscent of Cézanne's portraits of Madame Cézanne seated in front of a interior wall, such as Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune, 1888-1890. The composition of Portrait de femme au corsage bleu exhibits a similar treatment of the face, shown in asymmetrical features and brushstrokes of color defining the planes of the face.

Building on the influences of Picasso and Cézanne, Modigliani created a unique style of portraiture that utilizes a deeply hued palette, rich impasto, and linear drawing. While he incorporated external influences into his work, Modigliani based his portraits on keen observation of the sitter and their attributes. In the present work, the sitter's calm demeanor and tasteful wardrobe are clearly evident; however, the individualizing characteristics have been transformed and rendered immortal by the artist.

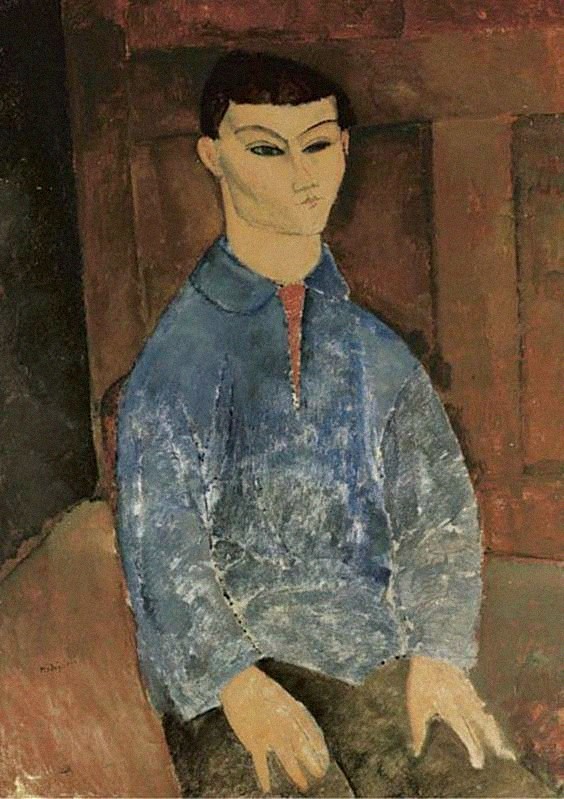

Moïse Kisling seduto (Moïse Kisling sitting)

1916, oil on board, 104.8 x 74.9 cm, Private Collection

The present painting is the largest of three portraits that Modigliani made of one of his closest friends, the Polish artist Moïse Kisling . Painted in 1915 and 1916, these images of Kisling are part of an important group of several dozen portraits by Modigliani that depict the artists, writers, dealers, and collectors who frequented bohemian Montparnasse during the war years. Taken together, these paintings constitute a veritable visual history of Left Bank culture in the second decade of the twentieth century.

When Modigliani moved to Montparnasse from neighboring Montmartre in late 1908 or early 1909, the neighborhood had already earned a reputation as the center of avant-garde artistic life in Paris. Lively, cosmopolitan, and sophisticated, Montparnasse was home to hundreds of artists and writers from dozens of different countries. The Café de la Rotonde, situated on the Boulevard du Montparnasse, functioned as the principal gathering place for this group, which included Picasso, Juan Gris, Diego Rivera, Chaïm Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, and Max Jacob, among many others.

Moïse Kisling, the subject of the present portrait, was another of the most popular figures in Montparnasse during this period . Born in Poland in 1891, he studied at the Kraków School of Fine Arts until 1910, when he moved to Paris. He settled at 3, rue Joseph Bara, a building occupied almost entirely by painters and sculptors.

Extroverted and generous, Kisling loved to play host, and his studio soon emerged as a favorite haunt for avant-garde artists, much like Picasso's apartment at the Bateau-Lavoir had been during the previous decade. Kisling also became one of Modigliani's closest friends and staunchest supporters. Starting in 1916, he shared his studio with Modigliani, even supplying the perennially impoverished painter with canvas and pigment. The two artists were frequently spotted together in the cafés and watering holes of the Left Bank, and a drawing by the Russian artist Maria Marevna shows them reveling with Soutine in Diego Rivera's studio in Montparnasse . In his biography of Modigliani, Pierre Sichel writes, "Less volatile than Modi, Kisling played as hard as he worked, chased the girls, drank, enjoyed parties and good times, but never became unhinged in the process. His exuberance and his magnificent gestures endeared him to Modigliani. There was the time he sold a painting for a hundred francs. Then, walking along the street with Modi, he spent all hundred on flowers which he impulsively gave to the women passing by--not just to pretty women, but to the ordinary, the young, the old, the beautiful, the ugly"

The present portrait is a striking character study of the young Kisling, depicted at the age of twenty-five. It shows him seated on a chair or stool, his hands in his lap and his torso turned at a slight three-quarter angle. In the background is what appears to be either a paneled door or the stretcher for a large canvas, propped upright against the wall. Kisling is clad in a blue artist's smock and simple, dark trousers. His expression is reserved yet guileless, and his posture is slightly ungainly. The physiognomic details of the portrait are unmistakably Kisling's, especially the wide brow with its thick fringe of dark hair.

1916, oil on board, 104.8 x 74.9 cm, Private Collection

The present painting is the largest of three portraits that Modigliani made of one of his closest friends, the Polish artist Moïse Kisling . Painted in 1915 and 1916, these images of Kisling are part of an important group of several dozen portraits by Modigliani that depict the artists, writers, dealers, and collectors who frequented bohemian Montparnasse during the war years. Taken together, these paintings constitute a veritable visual history of Left Bank culture in the second decade of the twentieth century.

When Modigliani moved to Montparnasse from neighboring Montmartre in late 1908 or early 1909, the neighborhood had already earned a reputation as the center of avant-garde artistic life in Paris. Lively, cosmopolitan, and sophisticated, Montparnasse was home to hundreds of artists and writers from dozens of different countries. The Café de la Rotonde, situated on the Boulevard du Montparnasse, functioned as the principal gathering place for this group, which included Picasso, Juan Gris, Diego Rivera, Chaïm Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, and Max Jacob, among many others.

Moïse Kisling, the subject of the present portrait, was another of the most popular figures in Montparnasse during this period . Born in Poland in 1891, he studied at the Kraków School of Fine Arts until 1910, when he moved to Paris. He settled at 3, rue Joseph Bara, a building occupied almost entirely by painters and sculptors.

Extroverted and generous, Kisling loved to play host, and his studio soon emerged as a favorite haunt for avant-garde artists, much like Picasso's apartment at the Bateau-Lavoir had been during the previous decade. Kisling also became one of Modigliani's closest friends and staunchest supporters. Starting in 1916, he shared his studio with Modigliani, even supplying the perennially impoverished painter with canvas and pigment. The two artists were frequently spotted together in the cafés and watering holes of the Left Bank, and a drawing by the Russian artist Maria Marevna shows them reveling with Soutine in Diego Rivera's studio in Montparnasse . In his biography of Modigliani, Pierre Sichel writes, "Less volatile than Modi, Kisling played as hard as he worked, chased the girls, drank, enjoyed parties and good times, but never became unhinged in the process. His exuberance and his magnificent gestures endeared him to Modigliani. There was the time he sold a painting for a hundred francs. Then, walking along the street with Modi, he spent all hundred on flowers which he impulsively gave to the women passing by--not just to pretty women, but to the ordinary, the young, the old, the beautiful, the ugly"

The present portrait is a striking character study of the young Kisling, depicted at the age of twenty-five. It shows him seated on a chair or stool, his hands in his lap and his torso turned at a slight three-quarter angle. In the background is what appears to be either a paneled door or the stretcher for a large canvas, propped upright against the wall. Kisling is clad in a blue artist's smock and simple, dark trousers. His expression is reserved yet guileless, and his posture is slightly ungainly. The physiognomic details of the portrait are unmistakably Kisling's, especially the wide brow with its thick fringe of dark hair.

Portrait of the Sculptor Oscar Miestchaninoff

Painted in 1916, oil on canvas, 81.2 x 65 cm, Private Collection

Depicting the sculptor Oscar Miestchaninoff, the present painting is one of an important group of several dozen portraits by Modigliani that record the artists, writers, dealers, and collectors who frequented bohemian Montparnasse during the war years. Taken together, these works constitute a veritable visual history of Left Bank culture in the second decade of the twentieth century

Oscar Miestchaninoff, the subject of the present portrait, was the son of a Jewish shopkeeper from the Russian town of Vitebsk. Born in 1886, Miestchaninoff studied sculpture briefly at the Odessa School of Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1909. He took an apartment in the Cité Falguière, an important artists' residence in Montparnasse, with numerous ground-floor studios that appealed especially to sculptors. Modigliani, who devoted himself almost exclusively to sculpture between 1909 and 1914, was already living at the Cité Falguière when Miestchaninoff arrived, and it is likely that the two artists met shortly thereafter. Miestchaninoff worked in a classicizing style and was one of the few non-Cubist artists whom Modigliani painted. He briefly attended classes at the École des Arts Décoratifs and the École des Beaux-Arts before enrolling in the Académie Russe, an independent artists' academy in Montparnasse that catered especially to Russian émigrés.

In the evenings, the Académie hosted open sketching sessions from a live model, which both Modigliani and Miestchaninoff's close friend Soutine are known to have frequented. Although his work is little known today, Miestchaninoff enjoyed a degree of professional and financial success during his lifetime, frequently exhibiting with other Jewish artists. He moved to the United States during World War II and remained there until his death in 1956.

The present painting is striking character study of the Russian sculptor, depicted at the age of thirty. It shows him seated with his hands firmly planted on his lap, a pose that recalls both Ingres's Monsieur Bertin and Picasso's famous 1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein (the latter painted while both Picasso and Modigliani were living at the Bâteau Lavoir in Montmartre). In contrast to his predecessors, however, Modigliani has positioned his sitter frontally, pushing Miestchaninoff's body close to the foreground plane and aligning him with the vertical and horizontal axes of the picture. The hieratic presence of the figure is relieved only by the slight tilt of the head and neck and by the subtle torsion of the shoulders and hips. The positioning of the hands suggests both confidence and a casual awkwardness on the part of the sitter. Miestchaninoff is clad in a blue mechanic's shirt, a garment that was favored by many artists in the Montparnasse circle. In 1916, the same year as the present work, Modigliani painted two portraits depicting the Polish artist Moïse Kisling, one of his closest friends, in a closely comparable pose and similar attire.

Painted in 1916, oil on canvas, 81.2 x 65 cm, Private Collection

Depicting the sculptor Oscar Miestchaninoff, the present painting is one of an important group of several dozen portraits by Modigliani that record the artists, writers, dealers, and collectors who frequented bohemian Montparnasse during the war years. Taken together, these works constitute a veritable visual history of Left Bank culture in the second decade of the twentieth century

Oscar Miestchaninoff, the subject of the present portrait, was the son of a Jewish shopkeeper from the Russian town of Vitebsk. Born in 1886, Miestchaninoff studied sculpture briefly at the Odessa School of Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1909. He took an apartment in the Cité Falguière, an important artists' residence in Montparnasse, with numerous ground-floor studios that appealed especially to sculptors. Modigliani, who devoted himself almost exclusively to sculpture between 1909 and 1914, was already living at the Cité Falguière when Miestchaninoff arrived, and it is likely that the two artists met shortly thereafter. Miestchaninoff worked in a classicizing style and was one of the few non-Cubist artists whom Modigliani painted. He briefly attended classes at the École des Arts Décoratifs and the École des Beaux-Arts before enrolling in the Académie Russe, an independent artists' academy in Montparnasse that catered especially to Russian émigrés.

In the evenings, the Académie hosted open sketching sessions from a live model, which both Modigliani and Miestchaninoff's close friend Soutine are known to have frequented. Although his work is little known today, Miestchaninoff enjoyed a degree of professional and financial success during his lifetime, frequently exhibiting with other Jewish artists. He moved to the United States during World War II and remained there until his death in 1956.

The present painting is striking character study of the Russian sculptor, depicted at the age of thirty. It shows him seated with his hands firmly planted on his lap, a pose that recalls both Ingres's Monsieur Bertin and Picasso's famous 1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein (the latter painted while both Picasso and Modigliani were living at the Bâteau Lavoir in Montmartre). In contrast to his predecessors, however, Modigliani has positioned his sitter frontally, pushing Miestchaninoff's body close to the foreground plane and aligning him with the vertical and horizontal axes of the picture. The hieratic presence of the figure is relieved only by the slight tilt of the head and neck and by the subtle torsion of the shoulders and hips. The positioning of the hands suggests both confidence and a casual awkwardness on the part of the sitter. Miestchaninoff is clad in a blue mechanic's shirt, a garment that was favored by many artists in the Montparnasse circle. In 1916, the same year as the present work, Modigliani painted two portraits depicting the Polish artist Moïse Kisling, one of his closest friends, in a closely comparable pose and similar attire.

Portrait of Beatrice Hastings

c. 1916, Oil on canvas, 43 x 27 cm

The young woman has pink skin, blonde wavy hair, up-turned nose, and a slightly open mouth. She is motioning outward energetically, a picture of youthful freshness. Modigliani’s portrait offers an enchanting peek into the personality of his lover. Beatrice Hastings arrived in Montparnasse in April 1914. She was a poet and correspondent for the English journal New Age. Sculptor Ossip Zadkine introduced the young English woman to Modigliani, who immediately fell in love with her, although their affair was brief. In numerous portraits, the human face and form remained Modigliani’s passion for the rest of his short life.

Born Emily Alice Haigh in South Africa in 1879, Beatrice Hastings came to Paris to write a column entitled "Impressions de Paris" for a London literary journal, The New Age. Max Jacob described her as "a great English poet...drunken, musical (a pianist), bohemian, elegant, dressed in the manner of the Transvaal and surrounded by a gang of bandits on the fringe of the arts. The details surrounding the start of Hastings' affair with Modigliani remain uncertain. The sculptor Ossip Zadkine and the English painter Nina Hamnett both claimed to have introduced the pair at the Café Rotonde in Montparnasse, probably in June of 1914. The American sculptor Jacob Epstein is also said to have had a hand in their meeting, according to an anecdote later published in the journal Paris-Montparnasse.

Modigliani's extraordinary portraits of Beatrice Hastings are now housed in major museum collections around the world, including the Barnes Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

c. 1916, Oil on canvas, 43 x 27 cm

The young woman has pink skin, blonde wavy hair, up-turned nose, and a slightly open mouth. She is motioning outward energetically, a picture of youthful freshness. Modigliani’s portrait offers an enchanting peek into the personality of his lover. Beatrice Hastings arrived in Montparnasse in April 1914. She was a poet and correspondent for the English journal New Age. Sculptor Ossip Zadkine introduced the young English woman to Modigliani, who immediately fell in love with her, although their affair was brief. In numerous portraits, the human face and form remained Modigliani’s passion for the rest of his short life.

Born Emily Alice Haigh in South Africa in 1879, Beatrice Hastings came to Paris to write a column entitled "Impressions de Paris" for a London literary journal, The New Age. Max Jacob described her as "a great English poet...drunken, musical (a pianist), bohemian, elegant, dressed in the manner of the Transvaal and surrounded by a gang of bandits on the fringe of the arts. The details surrounding the start of Hastings' affair with Modigliani remain uncertain. The sculptor Ossip Zadkine and the English painter Nina Hamnett both claimed to have introduced the pair at the Café Rotonde in Montparnasse, probably in June of 1914. The American sculptor Jacob Epstein is also said to have had a hand in their meeting, according to an anecdote later published in the journal Paris-Montparnasse.

Modigliani's extraordinary portraits of Beatrice Hastings are now housed in major museum collections around the world, including the Barnes Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

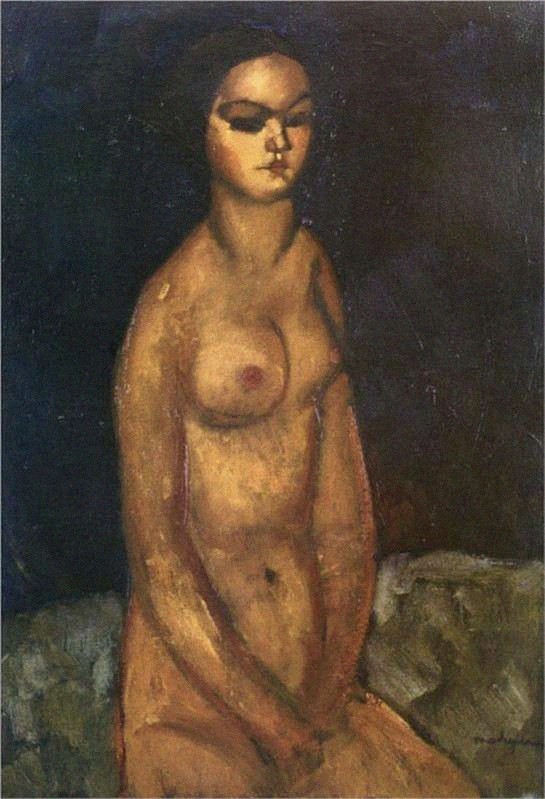

Seated nude

1908, Oil on canvas, 73 x 49.9 cm, Private Collection

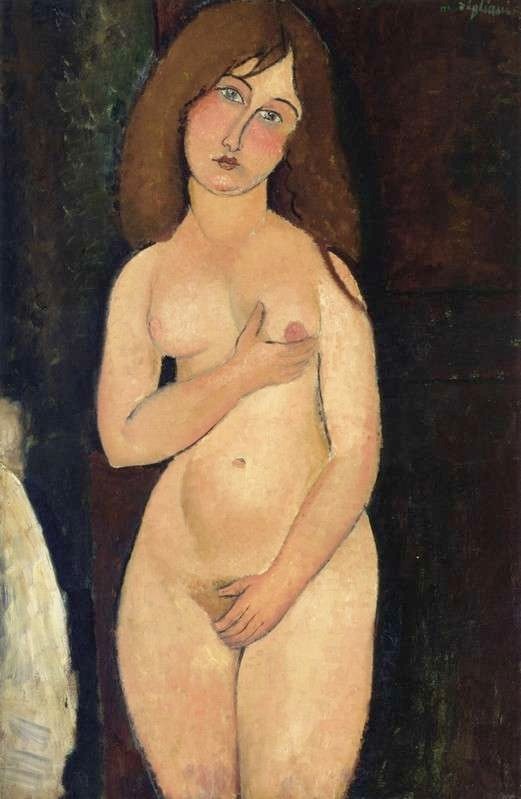

Modigliani had painted female nudes from the time of his arrival in Paris. His first works were notably expressive and conformed to the Symbolist idea of the female body as a source of sin. Later, his nudes lost this moralizing content and embraced a Mediterranean sensuality.

In 1917 and with the consolidation of his mature style, Modigliani began his popular series of reclining nudes on the request of his friend and new dealer, Léopold Zborowski, who aimed to sell them to collectors interested in the newest type of avant-garde art. However, the thirty or so works painted in Zborowski's apartment between 1917 and 1919 did not meet with the anticipated interest. In these works Modigliani looked to the example of earlier nudes, from Giorgione's Venus to Goya's Naked Maja, flattening the female form in a way first used by Ingres and ultimately adopted by Picasso. Most notable, however, is their erotic charge, which reflects the spirit of sexual liberty prevailing in Montparnasse in the second decade of the century and which shocked many of those who saw these paintings.

1908, Oil on canvas, 73 x 49.9 cm, Private Collection

Modigliani had painted female nudes from the time of his arrival in Paris. His first works were notably expressive and conformed to the Symbolist idea of the female body as a source of sin. Later, his nudes lost this moralizing content and embraced a Mediterranean sensuality.

In 1917 and with the consolidation of his mature style, Modigliani began his popular series of reclining nudes on the request of his friend and new dealer, Léopold Zborowski, who aimed to sell them to collectors interested in the newest type of avant-garde art. However, the thirty or so works painted in Zborowski's apartment between 1917 and 1919 did not meet with the anticipated interest. In these works Modigliani looked to the example of earlier nudes, from Giorgione's Venus to Goya's Naked Maja, flattening the female form in a way first used by Ingres and ultimately adopted by Picasso. Most notable, however, is their erotic charge, which reflects the spirit of sexual liberty prevailing in Montparnasse in the second decade of the century and which shocked many of those who saw these paintings.

Reclining nude with Arms Folded under Her Head

1916, Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 87 cm, Bührle Collection, Zurich, Switzerland

1916, Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 87 cm, Bührle Collection, Zurich, Switzerland

Nude on sofa (Almaisa)

1916, Oil on canvas, 81 x 116 cm, Private Collection

1916, Oil on canvas, 81 x 116 cm, Private Collection

Venus (Standing nude)

1917, Oil on canvas, 99.5 x 84.5 cm, Private Collection

Modigliani recalled from his student days in Florence, wandering about the Uffizi, the Medici Venus, a Roman copy done in the 1st century BC after a classic Greek marble. The Florentine painter Masaccio used this pose in his Expulsion of Adam and Eve, 1422-1426, in which the shamed, sinful Eve attempts to cover her nakedness as she is driven from the Garden of Eden. Botticelli, another Florentine master, revived the gesture of the Medici Venus in its original antique, pagan and sensual context for his famous Birth of Venus, also in the Uffizi.

Apart from his stylized caryatides after antique sources, Modigliani painted only four nudes before 1916. In 1916 Modigliani painted a seated nude and six reclining nudes. At the end of that year Zborowski and his wife moved to an apartment at 3, rue Joseph Bara, where they turned over one of their rooms to Modigliani for use as a studio. It was here that Modigliani painted Vénus, and the other great nudes, twenty in all, of 1917. Zborowski, by the terms of his contract, expected Modigliani to paint nudes. He knew that would they would be more commercially viable than straight portraits, and would offer the painter a challenge that was truly worthy of his talent and skill. Zborowski, in effect, commissioned the series of twenty nudes that Modigliani painted during this time, in some cases for his own collection, or more importantly, for use in his plan to promote the artist. Of the twenty nudes, thirteen are reclining and five are seated. In only two, including Vénus, is the model standing, in three-quarter length. Modigliani employed in them the same broad-hipped girl whose red hair no doubt reminded him of Botticelli's Venus. She appears nowhere else in the series.

1917, Oil on canvas, 99.5 x 84.5 cm, Private Collection

Modigliani recalled from his student days in Florence, wandering about the Uffizi, the Medici Venus, a Roman copy done in the 1st century BC after a classic Greek marble. The Florentine painter Masaccio used this pose in his Expulsion of Adam and Eve, 1422-1426, in which the shamed, sinful Eve attempts to cover her nakedness as she is driven from the Garden of Eden. Botticelli, another Florentine master, revived the gesture of the Medici Venus in its original antique, pagan and sensual context for his famous Birth of Venus, also in the Uffizi.