Sketcher, painter, engraver, sculptor and collector, Auguste Rodin is recognized worldwide for the exceptional authenticity of his anatomical sculptures. He strongly influenced twentieth century sculpture by his assemblage techniques and prepared the way for symbolism by adopting literary and mythological themes.

Born into a modest family, Rodin began drawing at the age of ten and four years later was accepted at a special school for drawing and mathematics called "La Petite Ecole”. There he discovered his passion for sculpture. After initial education, Rodin continued his studies with Antoine-Louis Barye and Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse; three attempts to enter the Ecole des Beaux Arts were unsuccessful. From 1872 to 1874 he went to Brussels and in 1875 to Florence and Rome where he was most impressed by Michaelangelo's work. Rodin kept contact with Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and with the Symbolists through Jules Dalou. From 1883 to 1889 he worked closely with Camille Claudel. Rodin, whose art, starting 1889, already met with great admiration, was considered by the turn of the century to be the leading modern French sculptor.

Auguste Rodin won many honours. He was named Knight, Officer, Commander and finally Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour. He also received several honorary doctorates from various universities.

Rodin published and exhibited very few of his drawings prior to 1897. Furthermore, drawings that relate to Rodin's own sculptures are extremely rare; most drawings related to sculptures are records of them after the fact, as opposed to preparatory studies. His earliest drawings were studies from classical sculpture, particularly those of Michelangelo, which he produced in order to understand the artists' conceptions of form. Rodin drew directly from models almost exclusively after 1890. According to Albert Elsen, "Drawing and modeling [his sculpture] were distinct yet mutually supportive and cross-fertilizing in his art. Seeing and feeling the model's profiles through the point of this pencil and hands gave conviction to his fingering of the clay and draftsmanship. Drawing made the body's contours instinctive for the sculptor; modeling taught the draftsman what was essential."

Drawing was his means of discovering "truth" in life and in art: "good" drawing represented truth and simplicity in nature; 'bad" drawing was self-conscious, mannered in its representation, and often displayed an ignorance of nature or inexact observation with attempts to mask it with artifice.

Rodin was a prolific draughtsman, producing some 10,000 drawings.. His drawings were seldom used as studies or projects for a sculpture or monument. Although the works on paper can only be shown periodically, owing to their fragility, the role they played in Rodin’s art was by no means minor. As the sculptor said at the end of his life:

“It’s very simple. My drawings are the key to my work.”

Born into a modest family, Rodin began drawing at the age of ten and four years later was accepted at a special school for drawing and mathematics called "La Petite Ecole”. There he discovered his passion for sculpture. After initial education, Rodin continued his studies with Antoine-Louis Barye and Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse; three attempts to enter the Ecole des Beaux Arts were unsuccessful. From 1872 to 1874 he went to Brussels and in 1875 to Florence and Rome where he was most impressed by Michaelangelo's work. Rodin kept contact with Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and with the Symbolists through Jules Dalou. From 1883 to 1889 he worked closely with Camille Claudel. Rodin, whose art, starting 1889, already met with great admiration, was considered by the turn of the century to be the leading modern French sculptor.

Auguste Rodin won many honours. He was named Knight, Officer, Commander and finally Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour. He also received several honorary doctorates from various universities.

Rodin published and exhibited very few of his drawings prior to 1897. Furthermore, drawings that relate to Rodin's own sculptures are extremely rare; most drawings related to sculptures are records of them after the fact, as opposed to preparatory studies. His earliest drawings were studies from classical sculpture, particularly those of Michelangelo, which he produced in order to understand the artists' conceptions of form. Rodin drew directly from models almost exclusively after 1890. According to Albert Elsen, "Drawing and modeling [his sculpture] were distinct yet mutually supportive and cross-fertilizing in his art. Seeing and feeling the model's profiles through the point of this pencil and hands gave conviction to his fingering of the clay and draftsmanship. Drawing made the body's contours instinctive for the sculptor; modeling taught the draftsman what was essential."

Drawing was his means of discovering "truth" in life and in art: "good" drawing represented truth and simplicity in nature; 'bad" drawing was self-conscious, mannered in its representation, and often displayed an ignorance of nature or inexact observation with attempts to mask it with artifice.

Rodin was a prolific draughtsman, producing some 10,000 drawings.. His drawings were seldom used as studies or projects for a sculpture or monument. Although the works on paper can only be shown periodically, owing to their fragility, the role they played in Rodin’s art was by no means minor. As the sculptor said at the end of his life:

“It’s very simple. My drawings are the key to my work.”

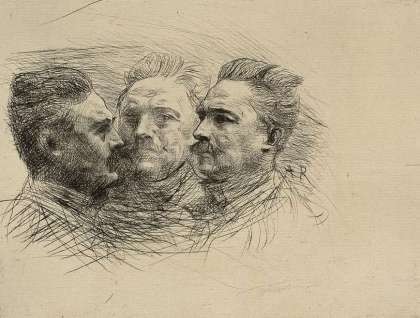

Portrait of Henri Becque

1883-87, Drypoint on cream laid paper, 14.9 x 19.5 cm

Rodin was introduced to copperplate engraving, or, to be more precise, to etching and dry-point engraving, in 1881, by his friend Alphonse Legros, then living in London. Although he soon mastered the technique, he only explored 13 subjects in his engravings, but often printed a large number of successive states. During his lifetime, the engravings he made after his portrait busts enabled him to familiarize the public with his freestanding sculpture and earned him an excellent reputation as an engraver. In the portrait of Henry Becque, Rodin placed a front view and two profile views of the writer side by side in the same copperplate, thereby multiplying the angles from which the sitter was seen and making him revolve around the sheet, like a bust placed on a sculptor’s turntable.

1883-87, Drypoint on cream laid paper, 14.9 x 19.5 cm

Rodin was introduced to copperplate engraving, or, to be more precise, to etching and dry-point engraving, in 1881, by his friend Alphonse Legros, then living in London. Although he soon mastered the technique, he only explored 13 subjects in his engravings, but often printed a large number of successive states. During his lifetime, the engravings he made after his portrait busts enabled him to familiarize the public with his freestanding sculpture and earned him an excellent reputation as an engraver. In the portrait of Henry Becque, Rodin placed a front view and two profile views of the writer side by side in the same copperplate, thereby multiplying the angles from which the sitter was seen and making him revolve around the sheet, like a bust placed on a sculptor’s turntable.

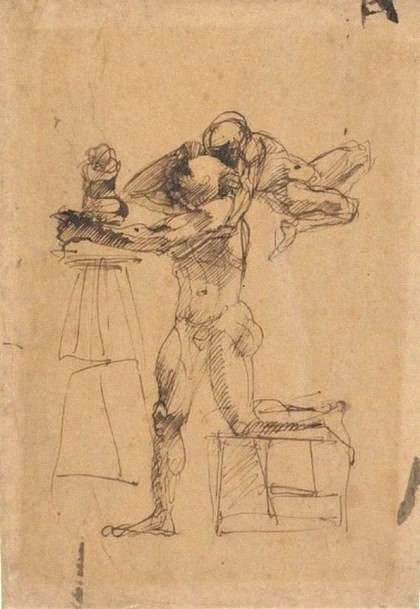

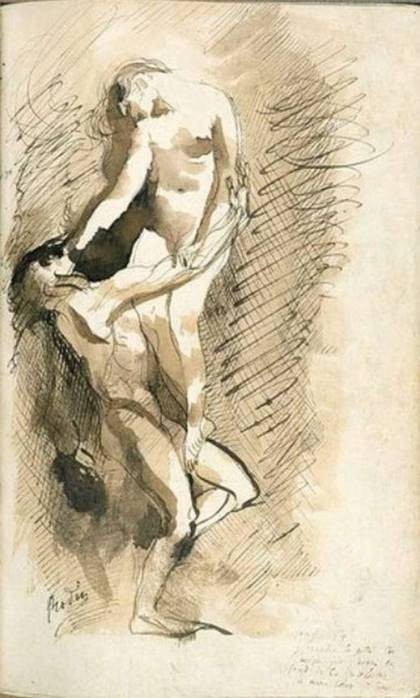

The Genius of the Sculptor

c. 1880-83, pen and brown ink, 26.3 x 18.9 cm

The Genius of the Sculptor treats an essential, self-referential theme in the art and life of Auguste Rodin. During his lifetime and afterward, he was viewed as the modern equivalent to the Renaissance genius of sculpture, Michelangelo. Moreover, Rodin repeatedly explored the theme of male creative genius in major works, such as the famous Thinker. In this drawing, Rodin depicted the artist in active thought with his hand on his head, accompanied by a wingless "genius" floating up from him. He derived this symbol of inner creative energy from the traditional subject of the winged muse descending to inspire.

c. 1880-83, pen and brown ink, 26.3 x 18.9 cm

The Genius of the Sculptor treats an essential, self-referential theme in the art and life of Auguste Rodin. During his lifetime and afterward, he was viewed as the modern equivalent to the Renaissance genius of sculpture, Michelangelo. Moreover, Rodin repeatedly explored the theme of male creative genius in major works, such as the famous Thinker. In this drawing, Rodin depicted the artist in active thought with his hand on his head, accompanied by a wingless "genius" floating up from him. He derived this symbol of inner creative energy from the traditional subject of the winged muse descending to inspire.

The Golden Age

c. 1878, Black chalk with white on gray paper,46.8 x 30.4 cm, Public Collection

The title, L'Age d'Or (The Age of Gold) refers to the Greek myth of the four ages of the world. During the first age, the Age of Gold, human beings were thought to have lived in a perpetual state of youthfulness, happiness, plenty, and peace. The third age, the Age of Bronze, when the first warlike men were thought to die by violence, was the origin of the title of one of Rodin's well-known sculptures.

c. 1878, Black chalk with white on gray paper,46.8 x 30.4 cm, Public Collection

The title, L'Age d'Or (The Age of Gold) refers to the Greek myth of the four ages of the world. During the first age, the Age of Gold, human beings were thought to have lived in a perpetual state of youthfulness, happiness, plenty, and peace. The third age, the Age of Bronze, when the first warlike men were thought to die by violence, was the origin of the title of one of Rodin's well-known sculptures.

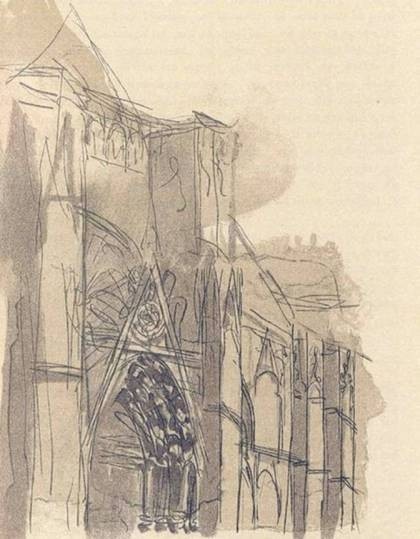

The Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Nantes

Plate III of Les cathedrales de France, published in an edition of 50 (Paris, 1914)

Les cathedrales de France, the book in which this plate was published, contains Rodin's musings on French medieval cathedrals accompanied by a hundred illustrations, largely of his sketches of details of French Gothic and Renaissance architecture. He also included a few illustrations identified as sketches made from works by Michelangelo. This illustration reveals Rodin's special interest in the play of light and shadow on the sculpture of the cathedral's portal.

Plate III of Les cathedrales de France, published in an edition of 50 (Paris, 1914)

Les cathedrales de France, the book in which this plate was published, contains Rodin's musings on French medieval cathedrals accompanied by a hundred illustrations, largely of his sketches of details of French Gothic and Renaissance architecture. He also included a few illustrations identified as sketches made from works by Michelangelo. This illustration reveals Rodin's special interest in the play of light and shadow on the sculpture of the cathedral's portal.

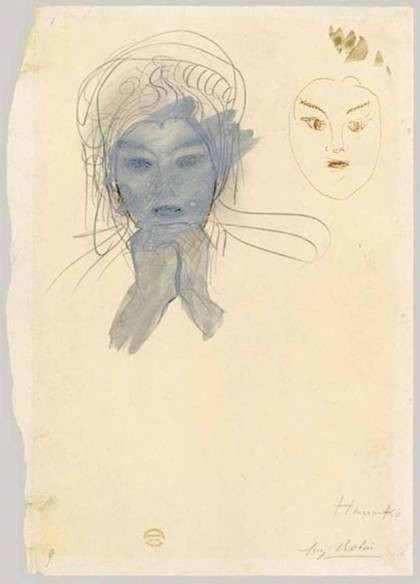

Hanako

c. 1908, Graphite, pen and brown ink, gouache and red chalk, 29.8 x 21.6 cm, Public Collection

The Japanese actress Ohta Hisa, known as Hanako, posed for a number of portrait studies, and Rodin portrayed her mobile face in various media. The pensive mood of the actress in this sketch is disturbed by the disquieting second image of her face as an enigmatic mask. Rodin apparently intended to use Hanako as a living model for a portrait of Beethoven, probably in much the same way that he had used a man of the city of Tours named Estager as the living model for the figure's head in the Monument to Balzac.

c. 1908, Graphite, pen and brown ink, gouache and red chalk, 29.8 x 21.6 cm, Public Collection

The Japanese actress Ohta Hisa, known as Hanako, posed for a number of portrait studies, and Rodin portrayed her mobile face in various media. The pensive mood of the actress in this sketch is disturbed by the disquieting second image of her face as an enigmatic mask. Rodin apparently intended to use Hanako as a living model for a portrait of Beethoven, probably in much the same way that he had used a man of the city of Tours named Estager as the living model for the figure's head in the Monument to Balzac.

De Profundis Clamavi

1887-88, Pen and brown ink, brown ink wash, 18.6 x12 cm, Public Collection

While Rodin stopped exploring the world of Dante and drawings from his imagination in the early 1880s, he remained faithful to the highly contrasted style of his “black drawings” and continued to use gouache and ink wash until the late 1880s. The perpetuation of this style is particularly noticeable in some of the ink drawings Rodin made for Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. Because he felt a special affinity with the poet and because he received a personal commission from Paul Gallimard, Rodin made 27 illustrations for the publisher and book lover’s own copy of the work, between October 1887 and January 1888 . Derived from earlier drawings inspired by Dante’s Inferno, the pose of these two lovers, whose bodies are modelled by a few shadows in wash, expresses all the pain and passion contained in Baudelaire’s verse, which Rodin carefully copied onto the bottom of the page.

1887-88, Pen and brown ink, brown ink wash, 18.6 x12 cm, Public Collection

While Rodin stopped exploring the world of Dante and drawings from his imagination in the early 1880s, he remained faithful to the highly contrasted style of his “black drawings” and continued to use gouache and ink wash until the late 1880s. The perpetuation of this style is particularly noticeable in some of the ink drawings Rodin made for Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. Because he felt a special affinity with the poet and because he received a personal commission from Paul Gallimard, Rodin made 27 illustrations for the publisher and book lover’s own copy of the work, between October 1887 and January 1888 . Derived from earlier drawings inspired by Dante’s Inferno, the pose of these two lovers, whose bodies are modelled by a few shadows in wash, expresses all the pain and passion contained in Baudelaire’s verse, which Rodin carefully copied onto the bottom of the page.

Astarte, after the Dancer Alda Moreno

c. 1912, Pencil and stumping, 20.1 cm x 31 cm, Public Collection

Seldom can Rodin’s models be identified. Circa 1910, he made the acquaintance of a Spanish dancer and acrobat working at the Opera Comique, called Alda Moreno, the forms of whose athletic body can be seen in about 50 drawings. These superb line drawings, on sheets larger than those Rodin ordinarily used, were executed in pencil and stumped so as to model the volumes of the body more accurately. The inscription, Astarte, made by Rodin to the acrobat’s right, identifies the female body with a star. Astarte or Ishtar, the daughter of the moon god and the twin sister of the sun, was worshipped as the goddess of Love and Desire in Mesopotamian mythology and assimilated to Aphrodite by the Greeks.

In this drawing, the dancer, whose acrobatic pose recalls a yoga position, seems to be hovering over the ground, rather like a flying saucer. The litheness of her body is accentuated by the excessive stretching movement of the supple arm. The extension of and amendments to the fingers touching the edge of the sheet, like the word bas inscribed by the artist on the right, illustrate Rodin’s habit of turning his drawings around to find a new direction for them, a new meaning.

c. 1912, Pencil and stumping, 20.1 cm x 31 cm, Public Collection

Seldom can Rodin’s models be identified. Circa 1910, he made the acquaintance of a Spanish dancer and acrobat working at the Opera Comique, called Alda Moreno, the forms of whose athletic body can be seen in about 50 drawings. These superb line drawings, on sheets larger than those Rodin ordinarily used, were executed in pencil and stumped so as to model the volumes of the body more accurately. The inscription, Astarte, made by Rodin to the acrobat’s right, identifies the female body with a star. Astarte or Ishtar, the daughter of the moon god and the twin sister of the sun, was worshipped as the goddess of Love and Desire in Mesopotamian mythology and assimilated to Aphrodite by the Greeks.

In this drawing, the dancer, whose acrobatic pose recalls a yoga position, seems to be hovering over the ground, rather like a flying saucer. The litheness of her body is accentuated by the excessive stretching movement of the supple arm. The extension of and amendments to the fingers touching the edge of the sheet, like the word bas inscribed by the artist on the right, illustrate Rodin’s habit of turning his drawings around to find a new direction for them, a new meaning.

Force and Ruse

c.1880, Pen and ink, wash and gouache on cardboard,15.5 x19.2 cm, Public Collection

The drawing representing the violence of a mythical coupling between a centaur and a woman. It is hard to distinguish whether what is depicted is the violence of an abduction or the fiery passion of a woman, ardently straddling the fabulous creature’s rump. Half-man, half-horse, the centaur, who represents the tumultuous battles between body and soul, between angel and beast, was one of Rodin’s favourite themes in the 1870s. Springing from the artist’s imagination, this work belongs to the period of his “black drawings”, even if it does not illustrate an episode from Dante’s Hell,but instead draws its inspiration from another of Rodin’s preferred books, Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

In this almost monochrome work featuring large, Michelangelesque bodies, the murky brown wash,mixed with gouache, conceals the lines drawn in pencil or ink, giving rise to a constant tension between form and haziness, intention and fate.

c.1880, Pen and ink, wash and gouache on cardboard,15.5 x19.2 cm, Public Collection

The drawing representing the violence of a mythical coupling between a centaur and a woman. It is hard to distinguish whether what is depicted is the violence of an abduction or the fiery passion of a woman, ardently straddling the fabulous creature’s rump. Half-man, half-horse, the centaur, who represents the tumultuous battles between body and soul, between angel and beast, was one of Rodin’s favourite themes in the 1870s. Springing from the artist’s imagination, this work belongs to the period of his “black drawings”, even if it does not illustrate an episode from Dante’s Hell,but instead draws its inspiration from another of Rodin’s preferred books, Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

In this almost monochrome work featuring large, Michelangelesque bodies, the murky brown wash,mixed with gouache, conceals the lines drawn in pencil or ink, giving rise to a constant tension between form and haziness, intention and fate.

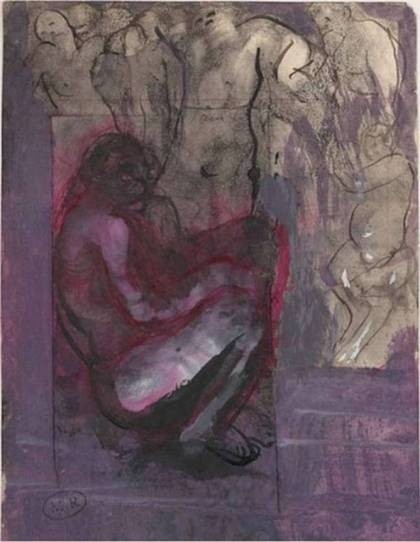

In the S...

c. 1880, Pencil, pen and ink, ink wash and gouache on paper mounted on ruled paper, 18,2 x 13,6 cm, Public Collection

This work on paper is one of the gouache or ink wash drawings that Rodin did while reading Dante’s Divine Comedy, in 1880-83. The central figure, curled up on himself, immersed in a sort of cesspool, is literally drowning in violet ink, while a procession of shades seem to observe him from above. Annotated in pen and ink on the right, dans la m..., this drawing recalls the meeting between Dante and one of the corrupters and flatterers, Alessio Interminei of Lucca:“And I, thence peering down, saw people in the lake’s foul bottom, plunged in dung... Searching its depths, I there made out a smeared head...”(Dante, Inferno, Canto XVIII).

The drawing, made on a fragile page from a notebook of ordinary paper, was subsequently cut out by the artist and stuck onto a larger sheet of paper. The consolidation of the original drawing at the same time enabled it to be enlarged, extended. This practice demonstrates how Rodin refused to “finish” a work, to consider it final. He was in the habit of reworking earlier drawings and combining them with new sketches, or new figures, as part of a metamorphic, cyclic process that would later reoccur in his sculptures.

c. 1880, Pencil, pen and ink, ink wash and gouache on paper mounted on ruled paper, 18,2 x 13,6 cm, Public Collection

This work on paper is one of the gouache or ink wash drawings that Rodin did while reading Dante’s Divine Comedy, in 1880-83. The central figure, curled up on himself, immersed in a sort of cesspool, is literally drowning in violet ink, while a procession of shades seem to observe him from above. Annotated in pen and ink on the right, dans la m..., this drawing recalls the meeting between Dante and one of the corrupters and flatterers, Alessio Interminei of Lucca:“And I, thence peering down, saw people in the lake’s foul bottom, plunged in dung... Searching its depths, I there made out a smeared head...”(Dante, Inferno, Canto XVIII).

The drawing, made on a fragile page from a notebook of ordinary paper, was subsequently cut out by the artist and stuck onto a larger sheet of paper. The consolidation of the original drawing at the same time enabled it to be enlarged, extended. This practice demonstrates how Rodin refused to “finish” a work, to consider it final. He was in the habit of reworking earlier drawings and combining them with new sketches, or new figures, as part of a metamorphic, cyclic process that would later reoccur in his sculptures.

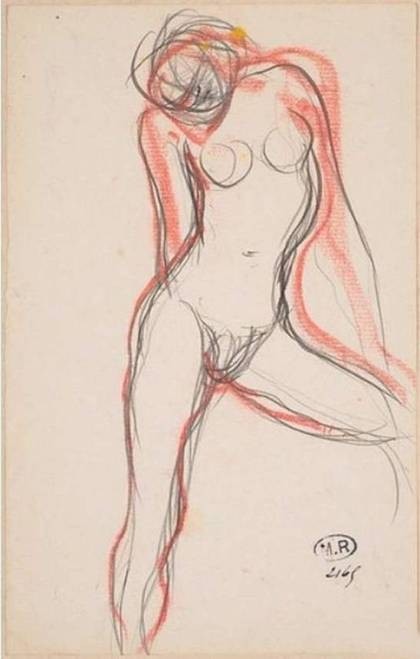

Female Nude with Left Leg Outstretched

c. 1890, Graphite pencil, brown ink, red pastel, pen, 20.2 x 12.7 cm, Public Collection

From 1890 onwards, as his reputation grew, the artist could at last afford to employ models on a regular basis. The female body, in all its many states, then became, with a few exceptions, his unique field of exploration. Forbidding any sort of pose, Rodin drew the model, asking her to move freely around his studio, and swiftly jotted down, with surprising vivacity, such and such a movement that seemed right or particularly expressive. There is nothing academic about Female Nude with Left Leg Outstretched. The insistent reworking of the contour lines and the amendments he made in strokes of red pastel attest to his desire to capture an authentic, expressive movement.

c. 1890, Graphite pencil, brown ink, red pastel, pen, 20.2 x 12.7 cm, Public Collection

From 1890 onwards, as his reputation grew, the artist could at last afford to employ models on a regular basis. The female body, in all its many states, then became, with a few exceptions, his unique field of exploration. Forbidding any sort of pose, Rodin drew the model, asking her to move freely around his studio, and swiftly jotted down, with surprising vivacity, such and such a movement that seemed right or particularly expressive. There is nothing academic about Female Nude with Left Leg Outstretched. The insistent reworking of the contour lines and the amendments he made in strokes of red pastel attest to his desire to capture an authentic, expressive movement.

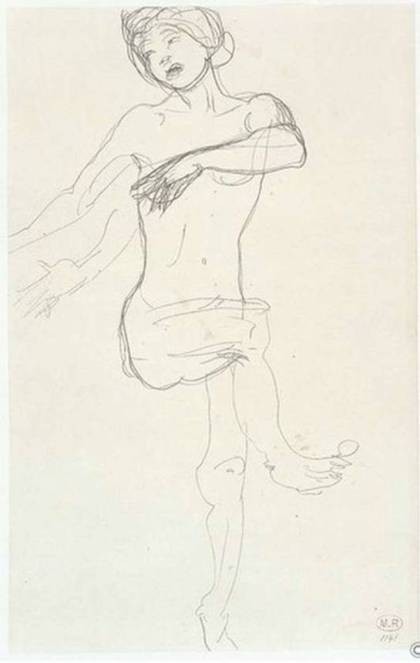

Hanako

1906-1907, Pencil on paper, 30.9 x 19.5 cm, Public Collection

This work on paper is one of the countless drawings sketched from life by Rodin, without taking his eyes off the model.

It is easy to recognize in this figure the Japanese actress Hanako, whom Rodin met in Marseilles in 1906. Fascinated by the expressivity of her face, the sculptor persuaded her to come and pose for him. He modeled 58 sculptures of Hanako, as well as a large number of drawings, made in a single sitting, during which he sought to capture her exceptional energy on his sheets of paper.

Rodin was struck by the powerful muscles of this tiny dancer’s “exotic” body, as he told Paul Gsell : “She is so strong that she can stand as long as she wants on one leg, while lifting the other in front of her at a right angle. She thus appears to be rooted to the ground like a tree”

1906-1907, Pencil on paper, 30.9 x 19.5 cm, Public Collection

This work on paper is one of the countless drawings sketched from life by Rodin, without taking his eyes off the model.

It is easy to recognize in this figure the Japanese actress Hanako, whom Rodin met in Marseilles in 1906. Fascinated by the expressivity of her face, the sculptor persuaded her to come and pose for him. He modeled 58 sculptures of Hanako, as well as a large number of drawings, made in a single sitting, during which he sought to capture her exceptional energy on his sheets of paper.

Rodin was struck by the powerful muscles of this tiny dancer’s “exotic” body, as he told Paul Gsell : “She is so strong that she can stand as long as she wants on one leg, while lifting the other in front of her at a right angle. She thus appears to be rooted to the ground like a tree”

Cambodian Dancer

1906, Graphite pencil, gouache, 31.3 x 19.8 cm, Public Collection

On 10 July 1906, Rodin, aged 66, attended a performance given in the Pre-Catelan, Paris, by a troupe of Cambodian dancers, who had accompanied King Sisowath of Cambodia on his official visit to France. Enthralled by the beauty of these dancers and the novelty of their movements, Rodin followed them to Marseilles to be able to make as many drawings of them as possible before they left the country on 20 July.

Rodin used gouache (ochre for the graceful arms and head, deep blue for the tunic draping the body), applied in broad brush strokes over and beyond the contour lines. All the details are eliminated (garments, face, hairstyle).All that remains is the concentrated energy of the graceful, eloquent, age-old gestures. “In short,” concluded Rodin, “if they are beautiful, it is because they have a natural way of producing the right movements”.

1906, Graphite pencil, gouache, 31.3 x 19.8 cm, Public Collection

On 10 July 1906, Rodin, aged 66, attended a performance given in the Pre-Catelan, Paris, by a troupe of Cambodian dancers, who had accompanied King Sisowath of Cambodia on his official visit to France. Enthralled by the beauty of these dancers and the novelty of their movements, Rodin followed them to Marseilles to be able to make as many drawings of them as possible before they left the country on 20 July.

Rodin used gouache (ochre for the graceful arms and head, deep blue for the tunic draping the body), applied in broad brush strokes over and beyond the contour lines. All the details are eliminated (garments, face, hairstyle).All that remains is the concentrated energy of the graceful, eloquent, age-old gestures. “In short,” concluded Rodin, “if they are beautiful, it is because they have a natural way of producing the right movements”.

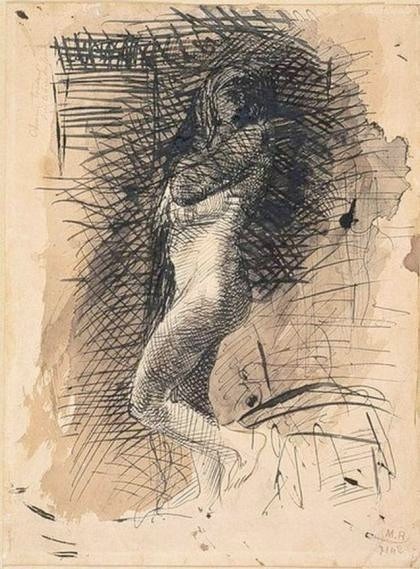

Eve

1884, Pen and black ink, brown ink wash on paper, 25.4 x 18.7 cm, Public Collection

Most of the drawings Rodin made in relation to his sculptures were not preparatory sketches, but drawings made after the sculptures once finished, generally as illustrations for a book or magazine article. This is the case here, since the present drawing, which borrows the pose of the sculpture Eve, dating from 1881.

1884, Pen and black ink, brown ink wash on paper, 25.4 x 18.7 cm, Public Collection

Most of the drawings Rodin made in relation to his sculptures were not preparatory sketches, but drawings made after the sculptures once finished, generally as illustrations for a book or magazine article. This is the case here, since the present drawing, which borrows the pose of the sculpture Eve, dating from 1881.

Male Nude, with One Hand and Knee on the Ground

1896-1898, Pencil and watercolour on paper, 32.5 x 25 cm, Public Collection

From 1896, Rodin only made drawings after a living model. He sought to capture chance movements, without taking his eyes off the model, without even glancing down at his sheet of paper. In this rare pencil drawing of a male nude, the erratic, initial lines of this “snapshot of a movement” are still visible. Rodin subsequently reworked and completed it with slashes of watercolour wash, a process Gsell described as follows: “The colouring of the flesh is dashed on in three or four broad strokes that score the torso and the limbs. These sketches fix the very rapid gesture or the transient motion which the eye itself has hardly seized for one half second. They do not give you merely line and colour: they give you movement and life”

1896-1898, Pencil and watercolour on paper, 32.5 x 25 cm, Public Collection

From 1896, Rodin only made drawings after a living model. He sought to capture chance movements, without taking his eyes off the model, without even glancing down at his sheet of paper. In this rare pencil drawing of a male nude, the erratic, initial lines of this “snapshot of a movement” are still visible. Rodin subsequently reworked and completed it with slashes of watercolour wash, a process Gsell described as follows: “The colouring of the flesh is dashed on in three or four broad strokes that score the torso and the limbs. These sketches fix the very rapid gesture or the transient motion which the eye itself has hardly seized for one half second. They do not give you merely line and colour: they give you movement and life”

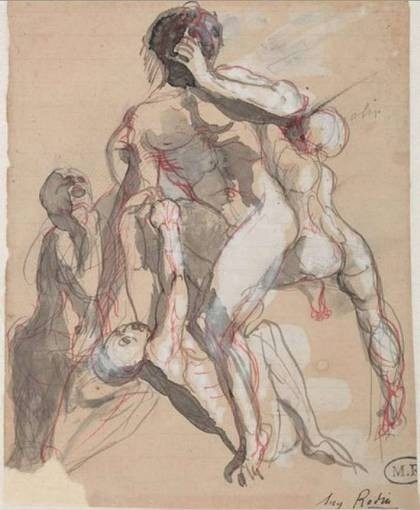

Ugolino surrounded by his Three Children

c. 1880, Pencil, pen and wash, ink and gouache on paper, 17.3 x 13.7 cm, Public Collection

When Rodin received the commission for The Gates of Hell, he immersed himself in Dante’s Divine Comedy, “pencil in hand”, and made over 100 drawings, which were not designs for the monument, but a means of “working in the spirit of this formidable poet”, as he wrote in a letter to Leon Gauchez. Invaded by dark lines or ink washes, these sketches became known as the “black drawings”, both because of the technique used and the infernal world they depict.

Among the desperate, endlessly wandering souls whom Dante and Virgil encounter during their journey, Ugolino was the one that especially fuelled Rodin’s imagination. The artist decided to follow all the episodes of the count’s tragic destiny, from his imprisonment in the Tower of Pisa, where he had been condemned to starve to death with his children, to the atrocious scenes in which he devoured his own sons.

In this pyramidal composition, the contorted bodies and screaming mouths are modelled by shadowy grey washes and white gouache highlights, while a mass of entangled lines in pencil or red ink confer a frenetic, bloodthirsty aspect on the scene. The turbulent, poignant nature of this image is heightened by the dark expression on the face of Ugolino, who, as his sons cling to his side, seeks to stifle a scream of terror with his left hand or to cover his ravenous mouth.

c. 1880, Pencil, pen and wash, ink and gouache on paper, 17.3 x 13.7 cm, Public Collection

When Rodin received the commission for The Gates of Hell, he immersed himself in Dante’s Divine Comedy, “pencil in hand”, and made over 100 drawings, which were not designs for the monument, but a means of “working in the spirit of this formidable poet”, as he wrote in a letter to Leon Gauchez. Invaded by dark lines or ink washes, these sketches became known as the “black drawings”, both because of the technique used and the infernal world they depict.

Among the desperate, endlessly wandering souls whom Dante and Virgil encounter during their journey, Ugolino was the one that especially fuelled Rodin’s imagination. The artist decided to follow all the episodes of the count’s tragic destiny, from his imprisonment in the Tower of Pisa, where he had been condemned to starve to death with his children, to the atrocious scenes in which he devoured his own sons.

In this pyramidal composition, the contorted bodies and screaming mouths are modelled by shadowy grey washes and white gouache highlights, while a mass of entangled lines in pencil or red ink confer a frenetic, bloodthirsty aspect on the scene. The turbulent, poignant nature of this image is heightened by the dark expression on the face of Ugolino, who, as his sons cling to his side, seeks to stifle a scream of terror with his left hand or to cover his ravenous mouth.

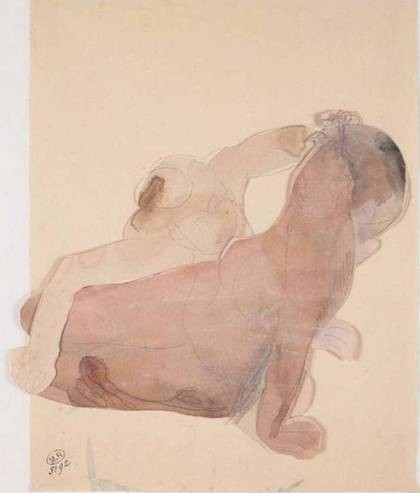

Torso of a Reclining Female Nude, with one Hand on her Chest

c. 1900, Pencil and stumping on paper, 20 x 31 cm, Public Collection

In the last years of his life, Rodin no longer contented himself with single line drawings, in fine dry pencil, covered with a light wash. He worked on the modelling with stumping, using his finger to crush a soft lead pencil to cloud over, or partially obliterate the pencil marks, to obtain hazier areas, with less contrast between the figure and the background. This return to a more naturalistic modelling is typical of Rodin’s late drawings.

Parallels can be drawn between the more or less pronounced sfumato, or misty unfinished effects, and the handling of the marbles, where figures gently emerge out of an indistinct background and echo the hazy monochrome paintings of Rodin’s great friend, Eugene Carriere.

c. 1900, Pencil and stumping on paper, 20 x 31 cm, Public Collection

In the last years of his life, Rodin no longer contented himself with single line drawings, in fine dry pencil, covered with a light wash. He worked on the modelling with stumping, using his finger to crush a soft lead pencil to cloud over, or partially obliterate the pencil marks, to obtain hazier areas, with less contrast between the figure and the background. This return to a more naturalistic modelling is typical of Rodin’s late drawings.

Parallels can be drawn between the more or less pronounced sfumato, or misty unfinished effects, and the handling of the marbles, where figures gently emerge out of an indistinct background and echo the hazy monochrome paintings of Rodin’s great friend, Eugene Carriere.

Two Semi-Reclining Female Nudes

c. 1900, Pencil and watercolour on paper, cut out and assembled, 32.6 x 26.2 cm, Public Collection

From 1900 onwards, when Rodin was particularly pleased with an attitude or movement in one or other of his drawings, he would sometimes cut it out to further experiment with it. He thus built up a stock of cut-out silhouettes, taken from his drawings. He would then select two or three of these figures and rearrange them in a new composition. Once he had decided on the arrangement, he would use tracing paper to transfer the composition onto another sheet of paper, to which he then applied watercolours.

Two Semi-Reclining Female Nudes resulted from the assemblage of two such forms. Rodin emphasized the relief of the composition by passing one of the women’s arms over the other one’s legs. Like all the cut-out paper figures in the museum collections, these were mounted on a support after the artist’s death.

Rodin probably intended to use this two-figure assemblage in a new watercolour. The idea of replacing brushes and pencils with a pair of scissors would later be widely echoed, particularly in the Cubists’ papiers colles, in the gouache-coloured paper cut-outs produced by Matisse in the last years of his life, and in the torn-up papers and drawings Hans Arp used as starting points for his Constellations, in the 1930s.

c. 1900, Pencil and watercolour on paper, cut out and assembled, 32.6 x 26.2 cm, Public Collection

From 1900 onwards, when Rodin was particularly pleased with an attitude or movement in one or other of his drawings, he would sometimes cut it out to further experiment with it. He thus built up a stock of cut-out silhouettes, taken from his drawings. He would then select two or three of these figures and rearrange them in a new composition. Once he had decided on the arrangement, he would use tracing paper to transfer the composition onto another sheet of paper, to which he then applied watercolours.

Two Semi-Reclining Female Nudes resulted from the assemblage of two such forms. Rodin emphasized the relief of the composition by passing one of the women’s arms over the other one’s legs. Like all the cut-out paper figures in the museum collections, these were mounted on a support after the artist’s death.

Rodin probably intended to use this two-figure assemblage in a new watercolour. The idea of replacing brushes and pencils with a pair of scissors would later be widely echoed, particularly in the Cubists’ papiers colles, in the gouache-coloured paper cut-outs produced by Matisse in the last years of his life, and in the torn-up papers and drawings Hans Arp used as starting points for his Constellations, in the 1930s.

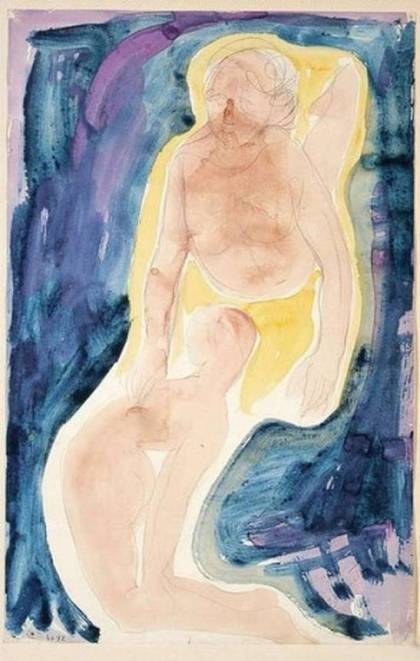

Resurrection

c. 1900, Pencil, watercolour and gouache on paper, 49.9 x 31.7 cm, Public Collection

As in his sculpture, Rodin experimented with combinations of figures in his drawings. This stunning composition thus resulted from the assemblage of two cut-out figures, probably traced from two separate drawings. As has been previously been seen, the two figures were then juxtaposed to give rise to a new work.

Through the addition of colour, Rodin then brought out the meaning he saw in this two-figure group. Applied in broad strokes of the brush thick with green, blue and purple gouache, the dark background seems to shrink back from the yellow halo that lights up the women’s bodies. Like an angel, one of them touches the other with her right hand and thus appears to draw her out of the darkness and bring her back into the light of life.

The annotation Resurrection, later added by Rodin, confirms this interpretation of the work, but his fundamental preoccupation lay elsewhere, as always in Rodin’s work, form was more important than subject.

c. 1900, Pencil, watercolour and gouache on paper, 49.9 x 31.7 cm, Public Collection

As in his sculpture, Rodin experimented with combinations of figures in his drawings. This stunning composition thus resulted from the assemblage of two cut-out figures, probably traced from two separate drawings. As has been previously been seen, the two figures were then juxtaposed to give rise to a new work.

Through the addition of colour, Rodin then brought out the meaning he saw in this two-figure group. Applied in broad strokes of the brush thick with green, blue and purple gouache, the dark background seems to shrink back from the yellow halo that lights up the women’s bodies. Like an angel, one of them touches the other with her right hand and thus appears to draw her out of the darkness and bring her back into the light of life.

The annotation Resurrection, later added by Rodin, confirms this interpretation of the work, but his fundamental preoccupation lay elsewhere, as always in Rodin’s work, form was more important than subject.

Les amants

c. 1910, watercolor and pencil on paper, 32.5 x 25 cm, Private Collection

c. 1910, watercolor and pencil on paper, 32.5 x 25 cm, Private Collection

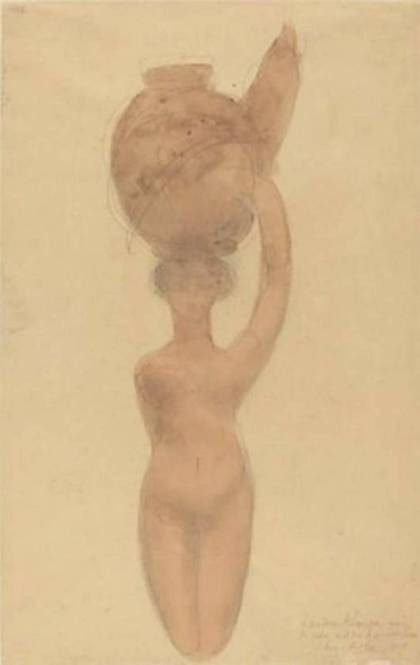

Nude Woman Carrying Vase on Head

1909, graphite and watercolor, 50.3 x 31.2 cm, Public Collection

1909, graphite and watercolor, 50.3 x 31.2 cm, Public Collection

RSS Feed

RSS Feed